The Abstract Wild

Jack Turner

Book Review

By Saam Shams,

April 5 2022

About the Author & Book

I could not find any biography about the author, Jack Turner, he does not appear to be advertised anywhere on the internet, no self promotion, or by others, which I find quite refreshing. It is almost as if the book is written by an anonymous author, the message he seeks to communicate has nothing to do with self promotion, in many ways he is doing the exact opposite.

A rock-climber from Boulder, Colorado, Jack Turner comes off as a sort of naturalist hippy, but when reading this work it is clear that he is a very thoughtful individual. A lifelong adventurer, the closest he came to modern civilized life was studying Philosophy at the University of Illinois, Chicago, as well as several failed marriages and attempts at ordinary jobs. He eventually left college before graduating to do some climbing around the Himalayas and return to the states to live as a climbing guide in Wyoming.

Turner was heavily influenced by the works of Henry David Thoreau. Also inspiring to Turner was the work of Arne Ness, titled, “The Shallow and Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movements: A Summary”. Turner has mentioned that the best modern continuation of the spirit of that work is in George Session’s recent collection, “Deep Ecology for the 21st Century.”

The book can be thought of as a series of essays that have been constructed over a long period of time influenced by the experiences and reflections of Turner. The strong opinions expressed by Turner come from a passion created by living a life in close contact with a wild & natural world few people now experience.

I must say that this book may be one of my all time favorites, as it more than anything I have read encapsulates best so many of my feelings and thoughts that come as a result of seeing beautiful natural places become overused and abused by a fun-seeking tourism industry with a seemingly endless appetite. Turner defends the spirit of wilderness better than anyone I know.

This book review is separated into different sections. Instead of a summarization of the book as a whole I examine different topics covered by Turner.

The Enemies of Wild

In the introduction Turner labels his enemies as abstractions, which abstract the wild. These abstractions include:

1) Diminished personal experience of nature;

2) Our preference for artifice, copy, simulation, and surrogate, for the engineered and the managed instead of the natural;

3) Our increasing dependence on experts to control and manipulate a natural world we no longer know;

4) Our addiction to economics;

5) The homogeneity that flattens not only biodiversity but cultural and linguistic diversity as Western thought, perception, production, and social structure spread across the globe;

6) Our increasing ignorance of what we have lost in sacrificing our several-million-year-old intimacy with the natural world.

The Maze

The book starts with a story of Turner’s youth when he explored the “Maze”, an untouched section of the canyon lands of eastern Utah, before the region was known and visited by tourists and even most people in the general region. “The Utah desert was relatively unknown in the early sixties...There were no guidebooks to these wild lands.” “Although the Maze was de facto wilderness, I did not then think of wilderness as a separate place needing preservation. The Wilderness Act was not passed until 1964.” He describes one encounter where he discovers some old pictographs drawn by Native Americans who used to inhabit the area which left a significant impression on him, believing that he was the first person to see them since those people have lived there.

When Turner returned to the Maze many years later the place he knew had permanently changed, “In may of 1995 I returned to the Maze. Things had changed. The Maze is now part of Canyonlands National Park, and the pictographs that so moved me are no longer unknown. They have a name – the Harvest Site (or Bird Site) – and they are marked on topographic maps.” Reflecting on the modern era Turner writes, “Virtually all of southern Utah is now photographed and exhibited to the public, so much so that looking at photographs or arches or pictographs, reading a guide book, examining maps, receiving instruction on where to go, where to camp, what to expect, how to act – and being watched over the entire time by a cadre of rangers – is now the normal mode of experience. Most people know no other.” “...southern Utah is no longer wild. Maps and guides destroy the wildness of a place just as surely as photography and mass tourism destroy the aura of art and nature. Indeed, the three together – knowledge (speaking generally), photography, and mass tourism – are the unholy trinity that destroys the mysteries of both are and nature.”

It is amazing to see the contrast of Turner’s experience in the maze from his youth where he spent days exploring with no access to the outside world, with his return in 1995 where he parked his truck, hung a camping permit, reserved a spot via phone paying with a Visa card. The wilderness aspect of the adventure was significantly eroded.

Escaping the West

Turner describes this mass exodus to Asia during the sixties and seventies by westerners as an event that significantly homogenized the world, and destroyed the very cultural differences that caused the desire of the migration to begin with. “In retrospect, Judith and Huntley and I were part of a modern exodus of hundred of thousands of Western people who left home and went to Asia. Some were hippies; some were pilgrims who ended up with Rajneesh in Poona, with Vipassana monks in the forest of Thailand, with Tibetan masters in Kathmandu, with Zen teachers in Kamakura; some were the first wave of what would become the adventure travel and ecotourism industries; some went to war in Vietnam; some went to the Peace Corps; some were merely ambassadors of capitalism and consumerism.”

Here turner writes how we basically need a new religion or world view to deal with the modern version of reality. “Between Newton and the present, the language of physical theory changed and our conception of reality has changed with it. Unfortunately, the languages of our social, political, and economic theories have endured despite achieving mature formulation before widespread industrialization, the rise of technology, severe overpopulation, the explosion of scientific knowledge, and globalization of economies. These events altered our social life without altering theories about our social life. Since a theory is merely a description of the world, a new set of agreements about the West requires some new descriptions of the world and our proper place in it.”

Turner vividly recalls a conversation with a Sherpa who was confounded by the sheer number of westerners desiring to visit the Himalayas, hearing about how beautiful their countries are. “I used to visit an old Sherpa in Khumbu who had served on perhaps fifty Himalayan expeditions. His name was Dawa Tensing and he lived in a village just north of Thyangboche Monastery on the trail to Everest. He was famous for saying, ‘So many people coming, coming, always looking, never finding, always coming back again. Why?’ Once in all sincerity, he asked me: ‘Is America Beautiful? Why you always come back here?’”

“Thoreau described ‘the West’ as ‘preparing to add its fables to those of the East. The valleys of the Ganges, the Nile, and the Rhine, having yielded their crop, it remains to be seen what the valleys of the Amazon, the Platte, the Orinoco, the St. Lawrence, and the Mississippi will produce.

Is it Just a Big Zoo?

A significant amount of the book is dedicated to the paradox of conservation programs such as the National Parks system and whether they actually support the conservation of wilderness or prioritize other motives such as economic activity. “The national parks were created for, and by, tourism, and they emphasize what interests a tourist – the picturesque and the odd.” “In Grand Teton National Park, 93 percent of the visitors never visit the back-country. If visitors do make other stops, it is at designated picturesque “scenes” or education exhibits presenting amusing facts – the names of peaks, a bit of history – or, very occasionally, for passive recreation, a ride in a boat or an organized nature walk.” “No one, for instance, is encouraged to climb mountains, backpack, or canoe alone. Hikers are discouraged from traveling off trail, especially in unpatrolled areas with difficult rescue. We are often prohibited from visiting remote areas where we might encounter bears.” “It is illegal to wander around the national parks without a permit defining where you go and where you stay and how long you stay. In every manner conceivable, national parks separate us from the freedom that is the promise of the wild.” “The rhetoric of preservation implies separation: we belong here, the grizzlies belong there. With this separation the National Park Service and the Forest Service – always with out welfare and welfare of wild animals and wild places in mind – prevent precisely the kind of experience that assumed fundamental importance not only in Peacock’s life, but in the lives of Thoreau, Muir, Leopold, Marshall, and Murie.

Turner compares the National Parks to zoos, just on a larger scale. “Yellowstone National Park is really a mega-zoo. Everything is exploited and managed now; it’s just a matter of degree. Accept this, It’s normal. We are doing it for the welfare of the animals and their home….Wild nature is not lost; we have collected it; you can go see it whenever you want.” “The bigger and more naturalistic the mega-zoo, the better the mask that conceals its reality as a prison for wild animals. I feel in some ways Turner is trying to say that for a creature to be wild, its destiny must not be determined by another.

Turner continues to describe his intense hatred for zoos, which is simply the inverse of his love of wild animals that are living freely in the wilderness. He describes a moment at the Sri Chamarejendra Zoological Garden (India) where he saw a mountain lion (an animal he has seen in the wild and reserves a fond love for) in a seemingly depressed state and he writes his state of emotion as, “I began to sink into that dead-end, rock-bottom, fuck-it pit of rage that is the trademark of my generation.” Some young Indian men came to the mountain lion and tormented it by throwing different grains at it, this caused turner to go into a rage and strangle one of them. After the incident he was recommended to leave the country.

Turner does not spare criticism of consumerism in the National Parks. “Muir could not have understood that setting aside a wild area would not in itself foster intimacy with the wild. His Yosemite Valley is now more like Coney Island than a wilderness. He could not have known that the organization and commercialization of anything, including wilderness, would destroy the sensuous, mysterious, empathetic, absorbed identification he was trying to save and express. He could not have known that even the wild would eventually succumb to consumer culture.” How many people who visit a National Park have a profound experience with a wilderness that changes who they are for the rest of their lives? And how many simply follow a tourist-book list of activities and finish with some purchases of gifts at the gift shop, almost as if they had just visited a theme park?

“The world of Thoreau and Muir – the mid-nineteenth century – was bright with hope and optimism. In spite of that, they were angry at the loss of the wild and expressed their anger with power and determination. Our times are darker. We understand the difficulties confronting preservation more thoroughly than they did. Their optimism seems impossible at the end of this century.”

Home

Turner examines our modern definition of home, “...we no longer have a home except in a brute commercial sense: home is where the bills come. To seriously help homeless humans and animals will require a sense of home that is not commercial.” Turner appears to suggest that “home” cannot be confined to a physical place or a structure, rather it is a sense of community, a membership to a society, which includes the natural world and wilderness.

Turner writes, “We know that the historical move from community to society proceeded by destroying unique local structures – religion, economy, food patterns, custom, possessions, families, traditions – and replacing these with national, or international, structures that created the modern ‘individual’ and integrated him into society. Modern man lost his home; in the process everything else did too.”

Flawed Economics

In describing the origins of our modern economic reality Turner writes, “Modern economics began in postfeudal Europe with the social forces and intellectual traditions we call the Enlightenment. On one level, its roots are a collection of texts. Men in England, France, and Germany wrote books; our Founders read the books and in turn wrote letters, memoranda, legislation, and the Constitution, thus creating a modern civil order of public and private sectors. Most of the problems facing my home today stem from that duality: water rights, the private use of public resources, public access through private lands, the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park, wilderness legislation, the private cost of grazing permits on public lands, military overflights, nuclear testing, the disposal of toxic waste, county zoning ordinances – the list is long. We are so absorbed by these tensions, and the means to resolve them, that we fail to notice that our maladies share a common thread – the use of the world conceived as a collection of resources.”

Turner goes on to describe how this economic reality forces us to maximize utility, and as a result diminish our sense of community and trust, “The decline in consensus also erodes trust. Trust is like glue – it holds things together. When trust erodes, personal relations, the family, communities, and nations delaminate. To live with this erosion is to experience modernity. The modern heirs of the Enlightenment believe material progress is worth the loss of shared experience, place, community, and trust. Others are less sanguine. But in the absence of alternatives the feeling of dilemma becomes paramount: most of us in the West feel stuck.” I can relate to the idea expressed here as I often feel a product of a machine designed to create productive humans that will produce “value”. All the years of schooling, working, and attempting to achieve a high position in the social hierarchy, it sometimes makes me feel like my life was designed for the purpose of extracting “material” or “economic” value out of me. Of course I think any functional society requires contribution from its members, but it is very different when that contribution is by choice and when it is part of a greater societal architecture. Turner continues, “If the religious purpose and sanction of the calling were to be removed from Locke’s theory, the purpose of individual human life and of social life would both be exhaustively defined by the goal of the maximization of utility. That’s where we are now. Instead of a shared vision of the good, we have a collection of property rights and utility calculations.” I am not sure I can think of a better definition of a religion that this statement, “a shared vision of the good.” Do we have a shared vision of the good? I really think this may be one of the most important questions of our modern world, and right now I don’t think we have an answer.

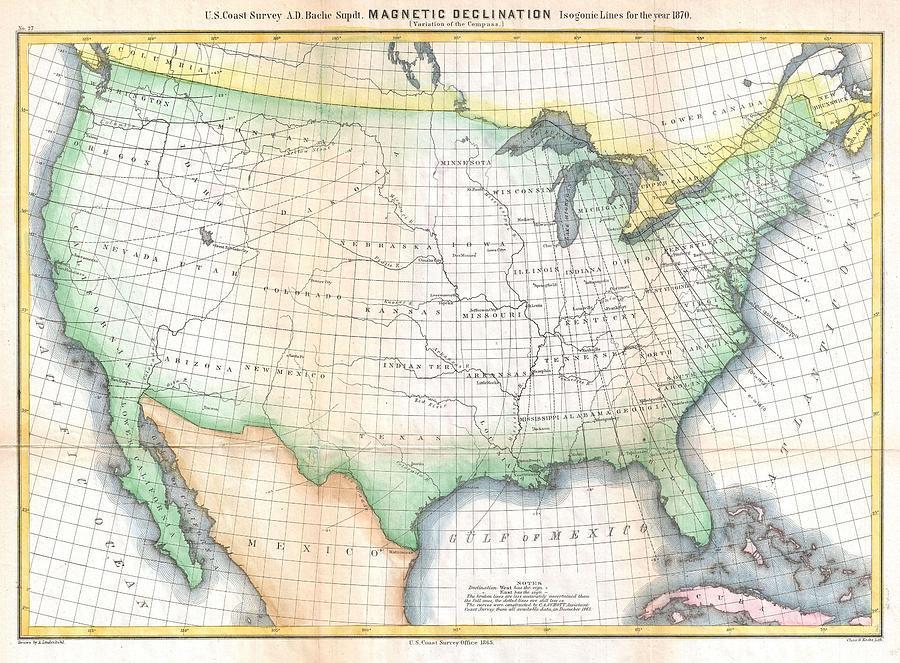

Turner describes how arbitrarily we have defined certain regions and divided our ownership of land, “The government’s great surveys redescribed the western landscape. In 1784 the federal government adopted a system of rectangular surveying first used by the French for their national survey. The result was a mathematical grid: six mile squares, one mile squares. Unfold your topo map and there they are, little squares in a matrix resembling a computer chip. The grid also produced rectangular farms, national parks, counties, Indian reservations, and states, none of which have any relation to the biological order of life.” “Things change. The little squares got smaller and smaller as the scale of the social order changed. First there was the section, then the acre, then the hundred-foot lot, then wall-to-wall town houses, then condos….Most people live in tiny rented squares and the ownership of sacred property is an aging dream.” “The idea that our social units should be defined by mathematical squares projected upon Earth from arbitrary points in space appears increasingly silly.”

There are a variety of opinions on how movements such as natural land conservation can operate under the current economic reality. Turner writes, “Many conservation and preservation groups now disdain moral persuasion, and many have simply given up on government regulation. Instead, they purchase what they can afford or argue that the market should be used to preserve everything from the ozone layer to biodiversity. They offer rewards to ranchers who allow wolves to den on their property, they buy trout streams, they pay blackmail so the rich will not violate undeveloped lands. They defend endangered species and rein forests on economic grounds. Instead of seeing modern economics as the problem, they see it as the solution.” “The new economic conservationists think they are being rational; I think they treat Mother Nature like a whorehouse.” I don’t really share Turner’s fairly extreme view here, he clearly seems to feel that our economic system is fundamentally flawed and there is no way of championing the environment while working within the confines of the system. I would argue there needs to be a balanced approach and to recognize that we do not value the natural ecosystem in our economic system (i.e. we do not pay bees for their work, sea life for giving us food, or the land for allowing us to grow crops), but we can make steps to incorporate it through actions such as regulation/taxation practices, or subsidizing economic activity that is considered eco-friendly. Turner writes, “Can the moral concerns of the West be resolved by economics? Can new incentives for recycling, waste disposal, and more efficient use end the environmental crisis? Can market mechanisms restore the quality of public lands? Does victory lie in pollution permits, tax incentives, and new mufflers? Will green capitalism preserve biodiversity? Will money heal the wounds of the West?”

Turner continues his tirade against our economic reality with the following statements: “...I believe classical economic theory, and all the theories it presupposes, is destroying the magical ring of life.” “Economics reduces everything to a unit of measurement because it requires that everything be commensurate – ‘capable of being measured by a common standard’” “Refuse these three moves – the abstraction of things into resources, their commensurability in translatable units, and the choice of money as the value of the units – and economic theory is useless.” Turner proposes that we can choose to not participate in this economic system (i.e. reject money) as a way to support the natural world and fulfill fundamental human needs. Turner wants to abandon economic theory as “It is the sickness of being forced to use language that ignores what matters in your heart.” According to Turner, “...our current economic practices are creating an unlivable planet.” Although I sympathize with Turner I feel that he has taken an extreme view and has not given enough thought and respect to the forces of economics that make our modern world function. He appears to have given up on finding any compromise and wants to completely remove it.

Limits to Rationality

Turner battles the concept of economic rationality by showing how they claim to rationalize love. The following quote is from Robert Nozick, in The Examined Life, where the concept of love is attempted to be explained in a manner to conform to economic rationality, “Repeated trading with a fixed partner with special resources might make it rational to develop yourself specialized assets for trading with that partner (and similarly on the partner’s part toward you); and this specialization gives some assurance that you will continue to trade with that party (since the invested resource would be worth much less in exchanges with any third party). Moreover, to shape yourself and specialize so as to better fit and trade well with others, you will want some commitment and guarantee that the party will continue to trade with you, a guarantee that goes beyond the party’s own specialization to fit you.”

Where does “irrational religion” fit into the modern rational economic reality? Turner argues that the United States evolved a “Protestant” perspective of religion. He writes, “The Sioux say the Black Hills are “sacred land,” but they found that “sacred land” does not appear in the language of property law. There is no office in which to file a claim for sacred land. If they filed suit, they’d discover that the Supreme Court tends to protect religious belief but not religious practices in a particular place – a very Protestant view of religion.”

Turner is clearly arguing that the human (and non human) experience cannot and should not be confined to a purely rational framework. I agree that much of our lives cannot be explained by rationality or logic. Why do we desire to live, love, or feel anything for that matter. All those why questions children ask, they seem to originate from some inherent irrationality, they seem to originate because we have developed a “rational” language that is trying to describe an “irrational” reality. Our rationality comes from observing the real constraints of the world around us, but our irrationality comes from within, our inner life force. And this thought is brilliantly expressed by Turner, in my favorite line of the book, “...Passion is at the root of all life and shared by all life. In passion, all beings are at their wildest; in passion, we – like pelicans – make strange noises that defy scientific explanation.”

Who is the wild for?

Turner explores a fascinating contradiction in two different groups that simultaneously support the wild and destroy it. “What is equally confounding is that people who have led a life of intimate contact with wild nature – a bucharoo working the Owyhee country, a halibut fisherman plying the currents of the Gulf of Alaska, an Eskimo whale hunter, a rancher tending a small cow/calf operation, a logger with his chain saw – often oppose preserving wild nature. The friends of preservation, on the other hand, are often city folk who depend on weekends and vacations in designated wilderness areas and national parks for their (necessarily) limited experience of wildness. This difference in degree of experience of wild nature, the dichotomy of friends/enemies of preservation, and the notorious inability of these two groups to communicate also indicate the depth of our muddle about wildness.” Those who regularly interact with the wild do not support preservation as their livelihood depends on their interaction with it. It would be the equivalent of preserving your home by not living in it. Those who are separated from the wild seek to preserve it and experience it during escapes from their domesticated lives far away from any resemblance of wilderness.

Turner makes several statements on the importance of wilderness for the soul of humanity. Turner writes, “Without big, wild wilderness I doubt most of us will ever see ourselves as part and parcel of nature.” Turner laments the fact that wilderness is rarely experienced by most people, writing “...the wilderness that most people visit (with the exception of Alaska and Canada) is too small – in space and time.” and “I am certain that less than one percent of our population has ever spent a day in truly wild country, and the number who have done so alone is infinitesimal.” Profoundly Turner states, “Nothing is more endangered than experience of the wild…” In my opinion, the wilderness experience is one of a sense of connection with all living creatures, to feel that your ‘community’ is life itself, and you are in the midst of a communal experience. Turner writes, “We return from the wild more capable of coping with the burdens of what Charles Taylor calls ‘ordinary life’ – our fundamental Puritan focus on work and family at the expense of nearly everything else.” In the wilderness, “...ecology is not studied, but felt, so that truths become known in the same way a child learns hot from cold – truths that are immune from doubt and argument and, most important, can can never be taken away.”

Wilderness Tourism

Turner brilliantly tackles the hypocrisy of tourism in the wilderness, often referred to as Eco-tourism.The following series of quotes speak for themselves: “All tourism is to some degree destructive, and wilderness tourism is no exception.”, “Wilderness tourism ignores, perhaps even caricatures, the experience that decisively marked the founders of wilderness preservation: Henry Thoreau, John Muir, Robert Marshall, Aldo Leopold, and Olaus Murie. The kind of wildness they experienced has become very rare – an endangered experience. As a result, we no longer understand the roots of our own cause.”, “Wilderness tourism is … devoted to fun. We hunt for fun, fish for fun, climb for fun, ski for fun, and hike for fun. This is the grim harvest of the ‘fun hog’ philosophy that powered the wilderness-recreation boom for three decades, the philosophy of Outside magazine and dozens of its ilk, and there is little evidence that either the spiritual or scientific concerns of the original conservationists – or the scientific concerns of the conservation biologists – have trickled down to most wilderness fun hogs.”, “Instead of a clash of needs, the preservation of the wild appears to be a clash of work versus recreation.”

Turner gets to the heart of the matter in this statement, “At the bedrock level, what drives both reform environmentalism and deep ecology is a practical problem: how to compel human beings to respect and care for wild nature.”

Its all about Control

The human desire for control is another important theme that Turner reflects on. Turner practically defines wilderness as a place that is not under the control of another, he writes, “A place is wild when its order is created according to its own principles of organization – when it is self-willed land”

Turner explores the paradox that virtually all of our methods for wilderness preservation are essentially methods of control, he writes, “To take wildness seriously is to take the issue of control seriously, and because the disciplines of applied biology do not take the issue of control seriously, they are littered with paradoxes – ‘wildlife management,’ ‘wilderness management,’ ‘managing for change,’ ‘managing natural systems,’ ‘mimicking natural disturbance,’ - and what we might call the paradoxes of autonomy.” “...the preservation of biodiversity becomes a problem like resource management. In the face of biodiversity loss (and there surely is such a crisis), conservation biology demands that we do something, now, in the only way that counts as doing something – more money, more research, more technology, more information, more acreage. Trust science, trust technology, trust experts; they know best. In short, the prescription for the malady is even more control.”

Turner’s suggestion is to escape the control impulse, which he seems to suggest is connected to Western Civilization (although I think it exists in the East as well), he writes, “...the preservation of wildness, wilderness, and biodiversity requires a revolution against social pathology, a transformation of Western Civilization – and let’s face it, most of us turn chicken in the face of the challenge. We prefer to control nature.” Turner examines our sense of ownership over nature, as some sort of “natural resource” we have control over. “The state owns all wild animals. Who gave it that power? Did we ever vote on it?”

Trusting the Experts

You could say that Turner has trust issues, but I would argue the entirety of modern society is having trust issues. Trust is a concept that Turner discusses at various sections of the book, it is critical to so many societal functions. In my longest selected quotation Turner writes, “This salvation implies trust in abstract systems, and since the lay person has neither knowledge or ability to evaluate the foundations of these abstract systems, our trust is less a matter of knowledge than that of faith. Those who are old-fashioned will place their trust in themselves and those they know instead of in abstract systems. Some will, of course, claim they are quite compatible, but in the last analysis they are not compatible: when push comes to shove, you must decide where to place your trust. Trust in abstract systems and experts disembeds our relations to nature from their proper context. This is precisely why so many of us will no longer place our trust in science: it ignores individual places, people, flora, and fauna. I, for one, do not want to know about grizzlies in general, nor can I in any practical way care about grizzlies in general. I want to know and care about the grizzly that lives in the canyon above me. And I have more trust in myself, my friends, and that grizzly than I do in the managers sitting in universities a thousand miles away who have never seen this place or this grizzly and want all of it subsumed by a mathematical model.” I find this a fascinating quote, it makes me ponder many questions. If you live in a remote and wild place you will undoubtedly encounter wild creatures, would you rather trust your own experience with these individual creatures, or would you trust the “expert” opinion on the general behaviors and habits of the creature’s species? Unlike Turner, I do think there is a middle ground here, I do think there is real knowledge and information collected and distributed by experts, but I also believe personal experience can override generalized knowledge, and you can distribute your trust how you like between yourself and an “abstract system”.

Turner continues his trust argument to argue that the management of wild lands cannot be trusted to experts, “The ‘preservation as management’ tradition that began with Leopold is finished because there is little reason to trust the experts to make intelligent long-range decisions about nature.”

Turner’s desire is ultimately to “Let wilderness again become a blank on our maps.”

He writes, “Why don’t the radical environmental organization push for that? I suspect a large part of the answer is this: there is no money in it, and like all nonprofits, they need a lot of money just to survive, much less achieve a goal.”

Complex Dynamic Systems

Both economic systems and ecological systems are complex dynamic systems. “Ecologists are compared with economists because of their problems with prediction.” Both are trying to predict/control an uncontrollable complex dynamic system, which defines living creatures.

The historian of ecology Donald Worster, in his essay ‘The Ecology of Order and Chaos,” notes that ‘Despite the obvious complexity of their subject matter, ecologists have been among the slowest to join the cross-disciplinary science of chaos’. This is not quite fair. Robert May, a mathematic ecologist at Oxford, is one of the pioneers of chaos theory, and his book Stability and Complexity in Model Ecosystems remains a classic. But Worster’s point is still telling, and one suspects that the ecologist’s lack of openness on the subject probably has something to do with the unsettling consequences for the practical application of their discipline – and hence their paychecks. They keep hanging on to the hope of better computer models and more information, but as Brecht said in another context, ‘If you’re still smiling, you don’t understand the news.’”

Complexity and chaos theory is the perfect support for Turner’s argument, he writes, “What emerges from the recent work on chaos and complexity is the final dismemberment of the metaphor of the world as machine, and the emergence of a new metaphor – a view of a world that is characterized by vitality and autonomy, one which is close to Thoreau’s sense of wildness, a view that, of course, goes well beyond him, but on he would no doubt find glorious.” In a way these theories quantify a world that cannot be predicted, cannot be fully understand, it is almost a paradox as we typically associate quantification with predictability and rationality. Turner writes, “Life evolves at the edge of chaos, the area of maximum vitality and change.” Indeed if we cannot understand or predict our ecosystem or economy, why are we trying to manage them? “...if such behavior does not allow long term quantitative predictions, then isn’t ecosystems management a bit of a shame?” The same can be said about the management of our economy.”

Select Quotes

“Attitude is merely a projection of one’s values…”

“...our ecological crisis is a crisis of character.”

“Emotion remains the best evidence of belief and value. Unfortunately, there is little connection between our emotions and the wild.”

“Wild things cannot be reached by travel.”

“I wish my neighbors were wilder.” - Henry Thoreau

“One of my heroes said he could imagine no finer life that to arise each morning and walk all day toward an unknown goal forever.”

“Imagine extending ‘community’ to include all the life forms of the place that is your home.”

“...reason alone is insufficient to move the will.”

“I believe all men are defined for life by how they spent their twenties.”

“As Thoreau said, there are enough champions of civilization. What we need now is a culture that deeply loves the wild earth.”

“We are more ignorant and limited than we can conceive. Even scientific descriptions and theories are contingent and subject to revision. We do not understand even our dog or cat, not to mention a vole. Even our knowledge of those we know best – our lovers and friends – is fragile and often mistaken. Our knowledge of strangers in our own culture is even more fragile, and it seems that despite our volumes of social science, we have no understanding of native peoples.”

“If I have an interest in preservation, it is in preserving the power of presence – of landscape, art, flora, and fauna. It is more complicated than merely preserving habitat and species, and one might suppose it is something that could be added on later, after we successfully preserver biodiversity say. But no, it’s the other way around: the loos of aura and presence is the main reason we are losing so much of the natural world.”

“Photographic reproduction and mass tourism are now commonplace and diminish a family of qualities broader than, though including, our experience of art: aura is affected, but so is wilderness, spirit, enchantment, the sacred, holiness, magic, and soul.”

“We lost the wild bit by bit for ten thousand years and forgave each loss and then forgot. Now we face the final loss.”

“The ‘normal’ wilderness – wilderness most people know – is a charade of areas, zones, and management plans that is driving the real wild in to oblivion.”

“Why do we associate the savage, the brutal, with the wild? The savagery of nature fades to nothing compared to the savagery of human agency. The most civilized nations on the planet killed sixty to seventy million of each other’s citizens in the thirty-year span from the beginning of World War I to the end of World War II. Dante, Shakespear, Goethe, Kant, Rosseau, Dogen, Mill, Beethoven, Back Mozart, Manet, Basho, Van Gogh, and Hokusai didn’t make any difference. The rule of law, human rights, democracy, the sovereignty of nations, liberal education, scientific method, and the presence of an Emperor God didn’t make any difference. Protestantism, Catholicism, Greek and Russian Orthodoxy, Buddhism, Shintoism, and Islam didn’t make any difference. How can we, at this time in history, think of a grizzly or a wolf as...savage? Why laugh at the idea of the noble savage when we have discovered no savage more savage than civilized man?”

“Unless we radically transform modern civilization, the wilderness and its people will be but a memory in the minds of people. When they die, it will die with them, and the wild will become completely abstract.”