Permaculture in a Nutshell

Patrick Whitefield

Book Review

By Saam Shams,

April 29 2022

Summary

This book was referred to me by a friend as a helpful book for people interested in learning about permaculture. Prior to reading this book I had never heard of the term “permaculture” although it sounds vaguely familiar for some reason. This is not a large book, only 84 pages long, with many of those pages containing large graphics. However, I found the book to take me longer than I anticipated to finish, because the concepts introduced in this book made me think deeply about my relationship to food, and indeed the relationship of all living things in an ecosystem. The author, Patrick Whitefield, is an Englishman and he wrote this book primarily to introduce permaculture to those living in England, however it is widely applicable to all temperate climates such as those in Europe and North America. I will complete this book review in the style of answering several questions, similar to how the author structured his chapters.

What is Permaculture?

The word “permaculture” is derived from “permanent agriculture”. However, in more recent times it has moved beyond the constraints of agriculture to include concepts such as town planning, water supply and purification, and commercial and financial systems. “It has been described as ‘designing sustainable human habitats’”.

Whitefield writes, “… permaculture is first and foremost a design system. The aim is to use the power of the human brain, applied to design, to replace human brawn or fossil fuel energy and the pollution that goes with it.” In many ways Permaculture is about efficiently using your land to create a self-sustaining ecosystem. This means efficient use of air space for cooling or heating, efficient design of agricultural lands to maximize food output and minimize water input with a sustainable mix of crops where fertilizer is not necessary, and an efficient system of human communal living to properly share responsibilities so that a sustainable life may be achieved without anybody living a standard of living similar to a peasant from the Middle Ages. But still, permaculture does not appear to have a specific definition, it is not just a design, not just a way to farm or grow plants, it encompasses many things together.

As Whitefield mentions, if you are doing any of the following you are already practicing permaculture:

- Enjoying the beauty of nature;

- Growing some of your own food;

- Walking, cycling or taking public transport instead of going by car;

- Making decisions about what you buy on the basis of how it effects the Earth;

- Reusing and recycling materials;

- Supporting nature conservation.

I have to admit I am not satisfied with this loose definition for permaculture (perhaps it is the engineer in me), it seems unconstrained, like it can almost mean anything. The following is my best attempt to define permaculture. Permaculture is the practice of living a sustainable life by redefining your relationship to your food, living space, and community by participating in a local ecosystem that can sustainably produce your needs for a healthy life while also contributing to the needs of a healthy ecosystem. If you think of the whole planet as one giant ecosystem it seems like we can take anything and not give back without any consequence, however when you think on a smaller scale there are direct and clear results and consequences from our contributions. Similarly, there are less societal rewards/consequences to behaving well/badly in large societies such as those of modern mega-cities as you will be a stranger to the majority of the population, however behavior in a small close-knit community will have a major effect on your status in that culture.

At the end of the day I believe permaculture is about finding a balance in how much we take from planet’s ecosystem, so that not only may we live healthy lives, but so that we may allow our planet to self-heal from a large period of time were humans have over extracted and damaged ecosystems around the planet with a long-lasting belief that there are virtually infinite resources available to extract.

How Did it Start?

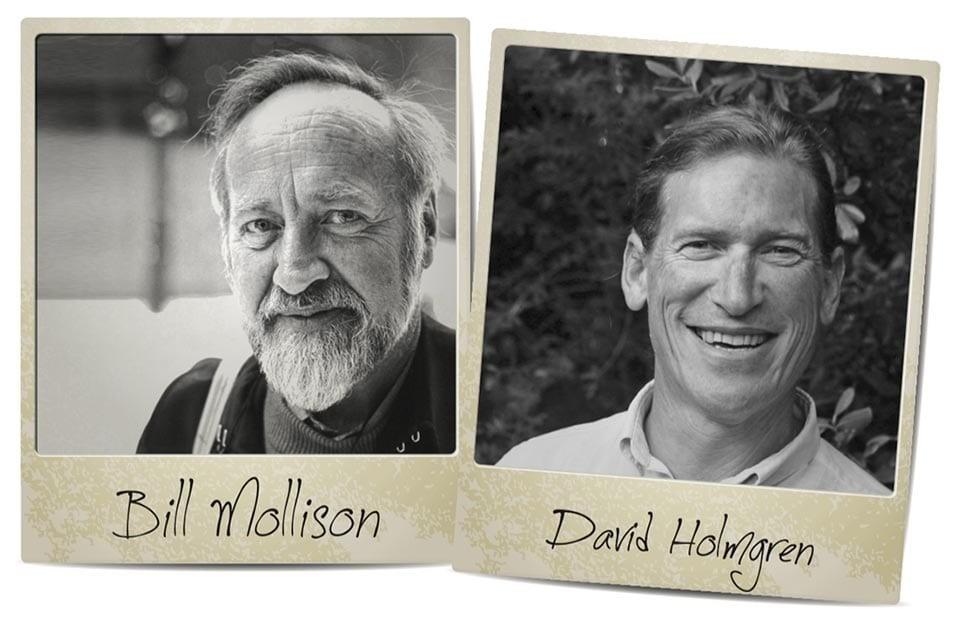

You can say that the practice of permaculture is as old as humanity, but the modern word was coined by two Australians, Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, when they wrote the book “Permaculture One” in 1978. “During the 1960s and 70s, Bill came to realise, as many of us did, that our present mainstream culture is heading down a blind alley, potentially a disastrous one. So he became involved in a lot of protesting, trying to persuade the people who are supposed to be running the world to put it to rights. After a while, he realised it was not getting him anywhere and he became convinced that real change takes place from the bottom up, not from the top down. So he gave up protesting, went home and gardened. And there permaculture was born.”

If there is a moral to this story it is that if you ever get stuck somewhere in your life, just go home and garden ☺. But in all seriousness this story reminds me of a quote I heard. Most people think you can change others, but you can’t, and that you can’t change yourself, but you can. This is a story of man trying to change something other than himself, although not another person, in a way society at large can be thought of as another person, he failed and chose to change himself instead, and by changing himself he started a movement that is making an impact on the world.

Why?

The case for permaculture goes something like this, by adopting permaculture we can:

- Increase the productivity of our land;

- Increase space for wilderness;

- Avoid damaging soil health and the desertification of large areas;

- Eliminate abject poverty;

- Create healthy communities where people have a feeling of belonging.

I feel compelled intuitively to the arguments poised by permaculture, but I can see some people viewing it as a step backwards, after all the technological process humans have made. Certainly, we have the technology and wealth to eliminate poverty and restore the health of the planet? I would pose that our technological advances are quite impressive, however it fails to grasp with the idea that we (as in humanity) are pretty much the same as the times of our distant pre-civilization ancestors. We crave a deep connection to the planet, we like all other living creatures need to be connected to the ecosystem to be healthy and live healthy lives. Our modern world has allowed an unimaginable number of humans to be alive at the same time on this planet, however the majority of these humans arguable do not live a life connected to their community, their food, or their natural surroundings. I am not convinced this trade-off is worth it.

Soil erosion alone is a reason to switch to permaculture. Whitefield writes, “In the state of Iowa, USA, it has been calculated that for every bushel of wheat produced six bushels of soil are lost by erosion. A third of the original topsoil on cropland in the United States is already gone. This is not farming, it is mining the soil.”

What Prevents Us from Making Progress?

Whitefield writes, “We largely know how we need to change our agriculture and industry in order to make them sustainable. How to deal with human emotions, such as fear and greed, is less simple however, and these are what really prevent us from making progress.”

I think this is a very powerful point. One can argue the primary reason nations and religions have traditionally encouraged large population growth is because of the constant fear of foreign invaders conquering the land. It is very possible that this fear of being destroyed is a primary driver in our behavior that is degrading the world’s ecosystem and ability to support life on the planet. Greed of course is another powerful force which also encourages the utilization of more resources than is necessary. How can we overcome these emotions? Perhaps we need a belief system or some ability to trust humanity to overcome these emotions? I think we tend to promote “hero” narratives of individuals who represent someone trustworthy, but perhaps there are other ways to achieve trust?

Permaculture in Practice

The second half of the book summarizes a variety of different permaculture applications. These include different ways to grow and raise chickens in a sustainable system, planting appropriate plants in different spaces to maximize output (i.e. sun friendly plants vs shade friendly plants), mixing plants to reduce pests and optimize soil health, growing native plants, combining fruit producing trees & bushes with a vegetable garden, designing efficient living space insulation, & using water efficiently.

The efficient design of a permaculture garden cannot be understated. As Whitefield writes, “A good designer will spend more time in listening to the landscape and its inhabitants, asking what each of them needs and has to offer, that in any other part of the design process.” It is also important to note the importance of water. Note only are “the most productive ecosystems on Earth are on the edges of water” but “a body of water can produce ten times the amount of protein in the form of fish, as the same area of grazing land can in the form of sheep or cattle.” Perhaps by this logic we should all be eating fish?

The advantage of having a nearby garden is also described by Whitefield, “The difference in food value between green vegetables which are eaten within minutes of being picked, and shop-bought ones, which were picked days before, is enormous. So vegetables that are grown very close to where they are eaten have a nutritional value out of all proportion to their bulk.”

Conclusion

I enjoyed reading this book. Despite its small size It is not the easiest book to read. Primarily in the second half of the book some pretty complicated and advanced permaculture concepts are introduced and I do feel that a better job could have been done to organize and simplify them to a reader not versed in agriculture or permaculture. I also feel that the general definition of permaculture needs to be redefined. Is permaculture a way to garden, is it a cultural phenomenon to create a community-based society, is it a new religion or philosophy to save the planet? Although I appreciate the idea of a “wholistic” concept where our humanity cannot be separated from an “objective” activity such as growing food from the earth, I think it is beneficial to separate these concepts so that we can better understand what it is that we are doing in a more objective way, before we impose our subjectivity, such as our desires for how the world ought to be or what it means to “care” for the planet, to be “healthy”, etc.