Americans in Persia

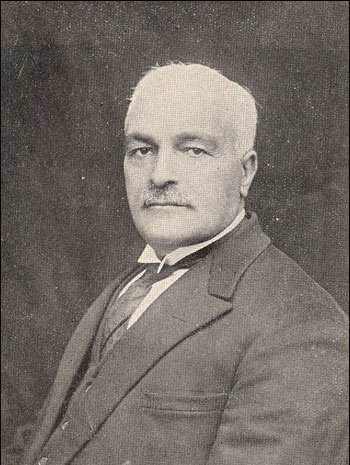

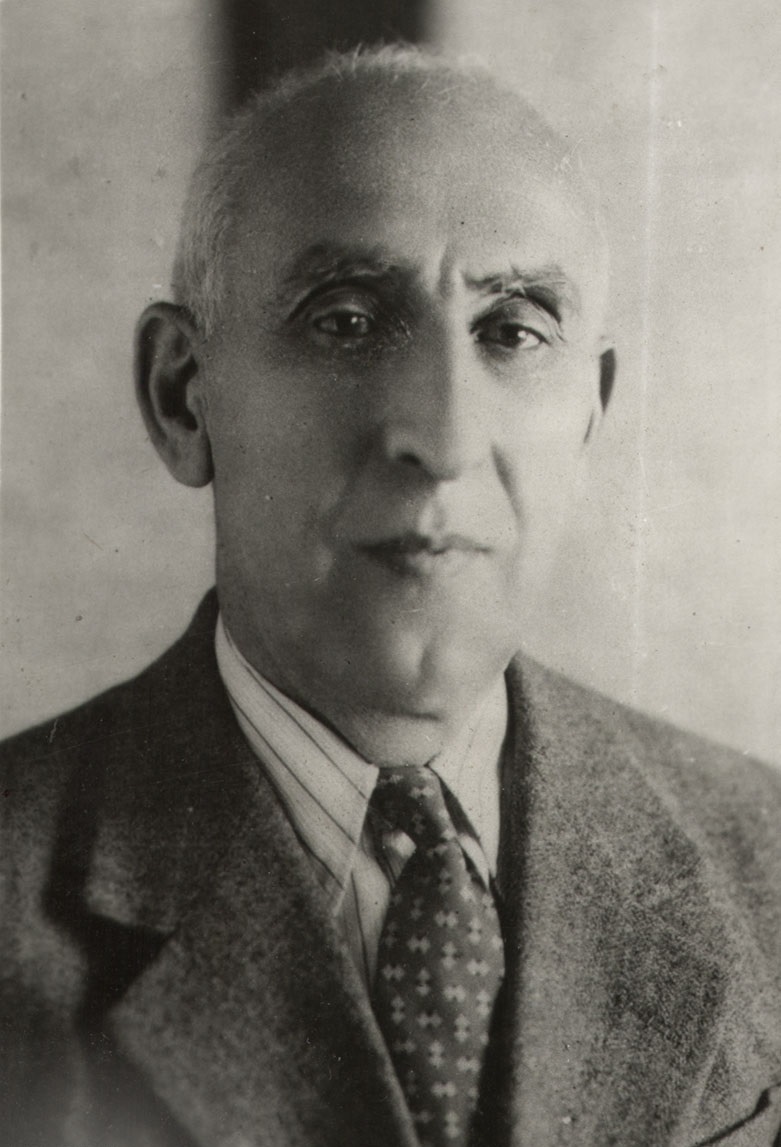

Arthur Millspaugh

Book Review

By Saam Shams,

June 21 2022

Summary

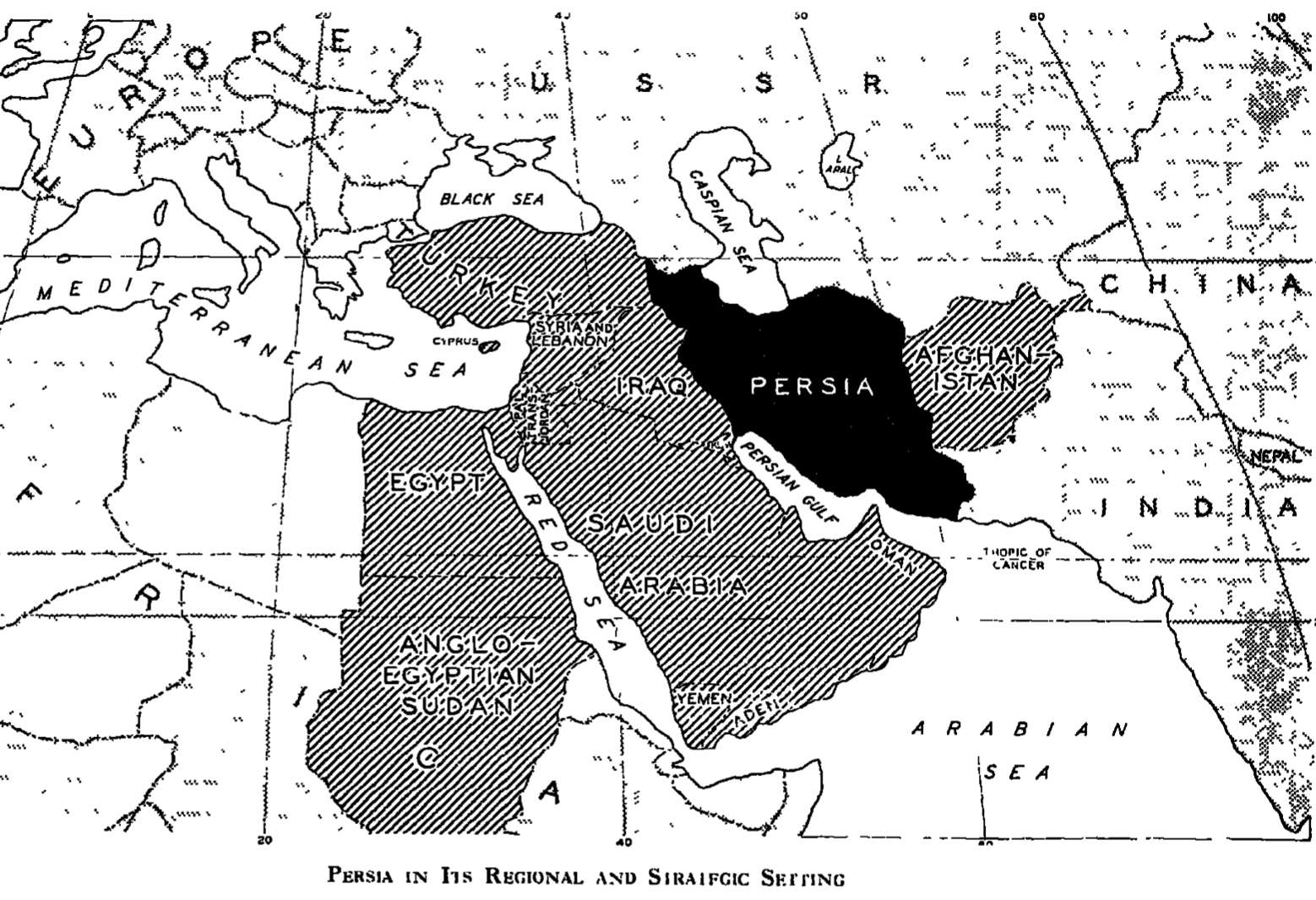

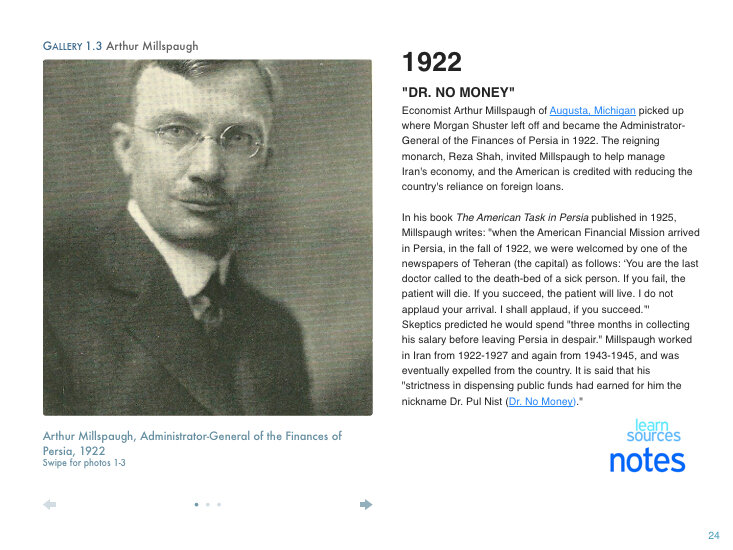

Arthur Millspaugh’s “Americans in Persia” is a memoir of the experiences and thoughts of Millspaugh’s time as Administrator General of the Finances of Persia. He had worked in Persia on two missions (from 1922-1927 and from 1943-1945), the book principally covers the second mission which happened during the second world war, in which Persia played the role of a weak but strategically important buffer state that is never quite sure of its neutrality.

This is a fascinating book for anyone interesting in understanding how the modern nation of Iran came to exist in the context of the modern nation state system that currently exists in the world. It follows the major economic and social changes which occurred to the country as it left the Qajar period and attempted to modernize and industrialize to become a modern nation state during the tumultuous period of the early to mid 20th century. In Millspaugh’s own words, “What is offered in this book amounts to a personal report on a problem area.”

What I find so refreshing about Millspaugh’s book is his unrelenting discussion of truths that he witnessed in his experience in Persia, particularly the difficult ones. Anyone with a deep emotional connection and a sense of pride in Persia (Iran) will have a difficult time reading this book, as it is hard not to see how utterly broken the country was and evidently continues to be to this day. These truths can destroy the illusions that create a sense of pride in the country, however I believe our imaginations are better used to imagine a better world for the future, rather than to hide inconvenient truths of the present or past. This way our imagination becomes a tool to motivate us to strive for our aspirations, rather than one that instills a false sense of pride that destroys our motivation for change.

The political game in Persia described in this book is one in which individuals are held to such a high standard that when an inevitable flaw appears they are attacked severely, creating a never-ending rotation in leadership. However due to the level of corruption this process did not encourage better leadership, but rather lifted people better at playing the bribery and corruption game.

I find it fascinating reading this book from the middle of the 20th century and thinking how much the world has changed now almost a quarter into the 21st century. In this book Millspaugh describes the primitive society he witnessed in Persia, with its attempt to instantly modernize from what he describes as the equivalent of English society in the 11th or 12th century. What fascinates me the most is not how Persia has failed to fully modernize and integrate into the society of developed nations but how American society has changed so much from this period where Millspaugh is writing from. The social changes that have occurred in the U.S. after the end of World War II have made the American civilization Millspaugh speaks of in this book appear to be a different country entirely. The level of thought, perspective, and sophistication in the writing of Millspaugh speaks of a country that has accepted a newfound role as world super power with a profound and sincere desire to make the world a better place. I do not see such qualities of leadership or character in the government of the U.S. at present to command such a role or to have an adequate vision of the future of humanity, let alone a vision to lead it. Furthermore, the deterioration of values in the larger U.S. society have eroded the social trust needed to have such an impactful and effective government. The social retardation Millspaugh speaks of in Persia at that time appears to have also occurred to the United States, perhaps it is now easier to imagine how at one time Persia could have been the center of power and civilization several thousand years ago.

About the Author

Arthur Millspaugh (1883-1955) was born on a farm in Augusta, Michigan, a town of less than 1,000 residents on the 2010 census survey. Millspaugh excelled in school from a young age, and went on to receive a Ph.D from Johns Hopkins University where his dissertation was a study of the effects of legislation and the political machinery within the state of Michigan. From a young age he had an interest in political science and economics, and many of his classmates predicted that he would end up in congress, but his career instead took him to work for the U.S. State Department Office of the Foreign Trade, and was eventually hired by the government of Persia (Iran) to be the Administrator General of Finance from 1922-1927 and 1942-1945. He had a profound impact on the development of Persia during the first half of the 20th century. My personal judgement from reading this book is that he was a man of integrity and a profoundly thoughtful person.

Iran or Persia?

The historical context provided in this section is from my own research and not from Millspaugh’s book, but I believe it helps to understand the terminology.

“A year or two after Shah Reza took the throne in 1926, he decreed that Persia should be known as Iran.” Eventually the government permitted the use of Persia again in 1941, but would be come to be known as Iran never the less. The region had been called Iran by Iranians since antiquity, however for the purposes of this book and book review Iran and Persia can be considered fully interchangeable. The term Iran is likely a Middle Persian modification of the ethnic term “Aryan”, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran_(word). This is the ethnic term used by the majority of the population in the modern nations of Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan to identify themselves. This is also the term used by Achaemenid kings to describe themselves as evident from cuneiform inscriptions left from antiquity. An example of this evidence is the wall inscriptions left to commemorate Darius I (550-486 B.C.) at “Naghsh-e-Rostam”, where part of the inscription translates to: “I am Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries containing all kinds of men, king in this great earth far and wide, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenid, a Persian, son of a Persian, an Aryan, having Aryan lineage.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naqsh-e_Rostam).

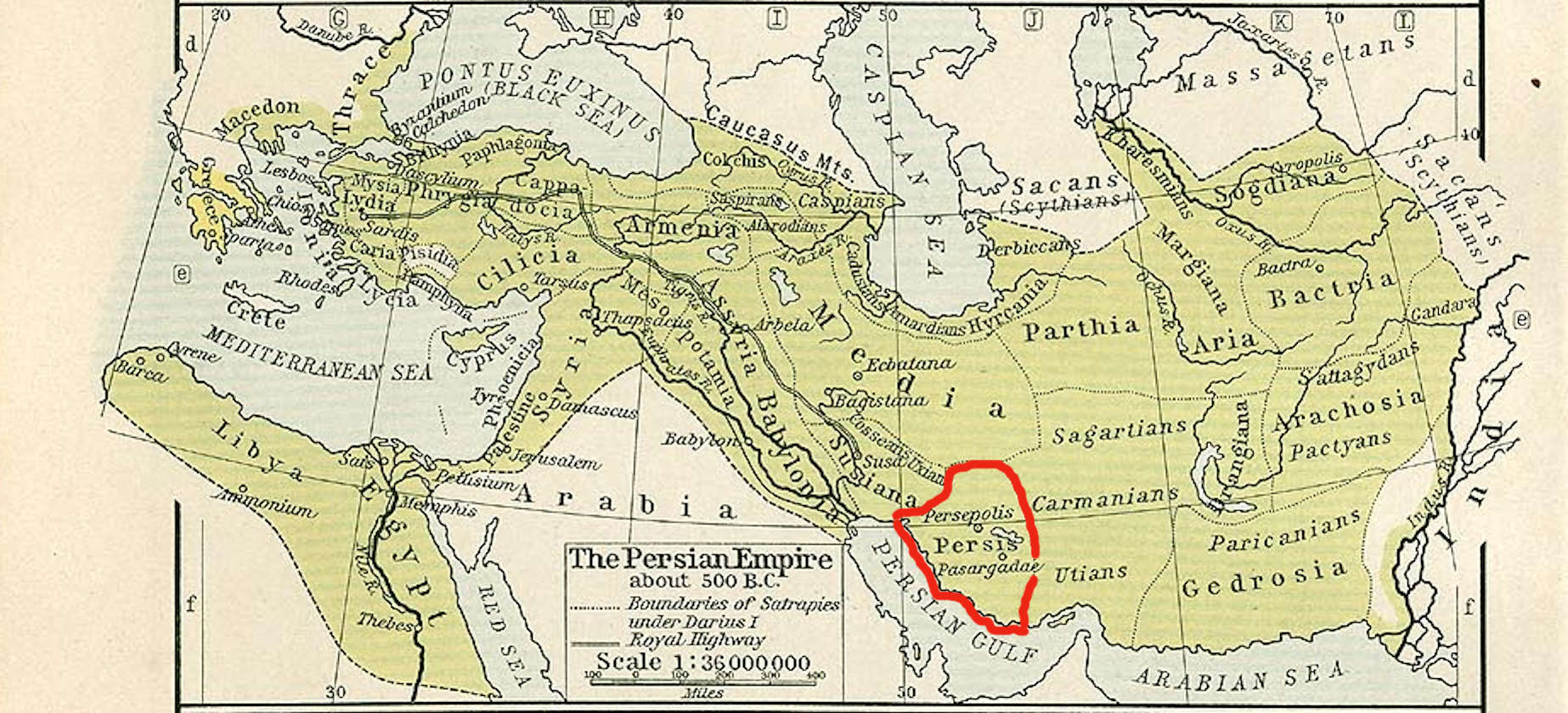

The term Persia is the English translation from the Greek “Persis” which is how the Greeks came to call the entire Achaemenid Empire and its population, but in actuality “Persis” or Persia, is was just a small part of the Achaemenid Empire and the Iranian world. The empire likely became known as Persian as the founder King Cyrus hailed from the region of Persia.

A Map Depicting the maximum extent of the Achaemenid Persian Empire approximately 500 B.C., with a circle highlighting the region of Persia.

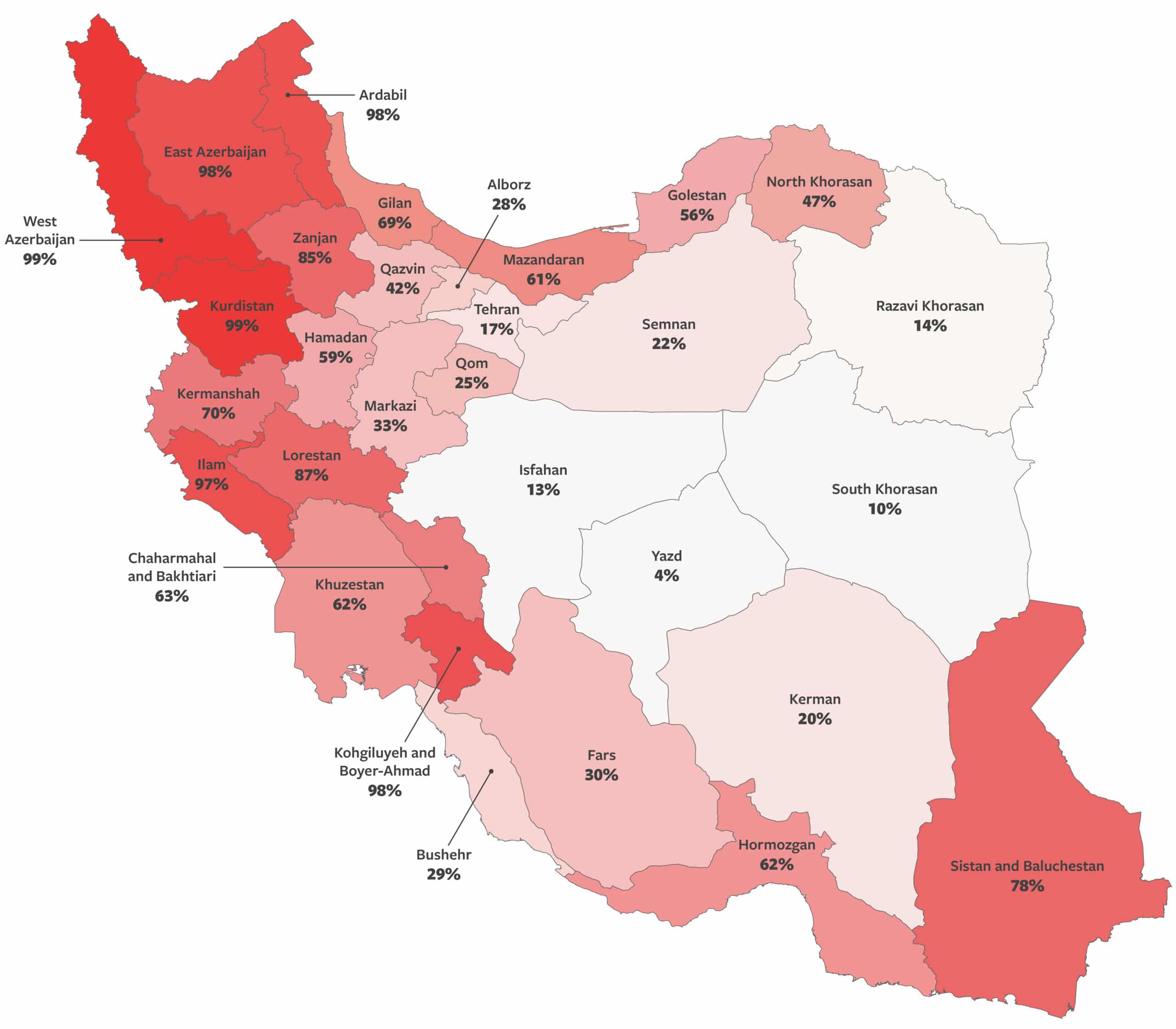

Those who study history will know that the modern region of Iran which bears that name is “Fars” and only represents a small part of the country of Iran and only a small portion of the larger Iranian ethnicity and culture. However perhaps due to the prestige of the ancient Achaemenian empire (which came to be known as the Persian Empire) many Iranians to this day like to call themselves Persians to be connected to that old empire. The closest analogy I can think of is if Italians preferred to be called Romans even if they had no connection to the city of Rome or its region, just so they could be associated with the Roman Empire.

A map depicting the modern states of Iran, “Fars” or “Persia” is located in the Southwest.

Note that the region used to be called “Pars” but had the letter P changed to F post Islamification of the region as the Arabic alphabet does not have a letter P. The language of the country (Farsi) is also associated with Pars, as it would be called “Parsi” without the modification to allow Arabic speakers to pronounce it.

The Persian Problem

This term, “The Persian Problem”, is mentioned many times in the book. So, what is “The Persian Problem”? More or less, it represents the fact that the Persia is in many ways a country of disfunction and chaos yet is located in one of the most strategically important locations in the world. Persia connects the larger Middle East (a landmass larger than the continental United States) to Asia, it connects the Caucuses, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia to the Middle East, it connects the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf, it connects a large variety of diverse cultures and ethnicities, it contains a significant amount of natural resources, and it borders the Persian Gulf which harbors the majority of crude oil shipments around the world. A truly globalized world cannot function without a functional nation where Persia is located. Persia was never truly colonized by any foreign power in modern times. However, with the end of World War II, the United States of America became the most powerful nation on the planet, supplanting the British with their dying global empire. It became a goal of American foreign policy to lead the world into an era of globalization via global trade and freely navigable ocean shipping routes. In this world, the Middle East, and Persia, play a critical role. Solving the Persian Problem meant ensuring a strong and competent government in Persia to allow free trade and competition for capital in a part of the world with little to no exposure to modern industrial life, living more or less as if nothing had changed since the 10th century A.D.

Qajar Persia (1789-1925)

The beginning of the 20th Century saw the end of the Qajar period for Persia. The Qajar tribe is a tribe with Turkish roots which ruled Iran for a period of 136 years. During the Qajar period rule over much of the Caucuses (including modern day eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan, and Armenia) was lost to Russia.

In the late 19th century there were signs of immense corruption in the Qajar leadership and significant discontent among the Persian population. “The tobacco monopoly, given to a British subject in 1890, caused an actual uprising that forced the cancellation of the grant. Nasr ud Din Shah died by assassination in 1895; his successor Muzaffar ud Din, weak-willed and broken in health, followed his father on the road to ruin. By 1906 the last straw had been placed on the camel’s back and revolution came.”

Nasr ud Din Shah

“In 1901, Muzaffar-ud-Din Shah granted to a British subject, W.K. D’Arcy, an oil concession that covered the whole of Persia except the five northern provinces…Just before the first world war Broke out, the British government acquired a controlling interest in the company’s capital stock.” The Qajar period does not appear to be one of prosperity for Persia or a memorable one.

W.K. D’Arcy

Muzaffar-ud-Din Shah with Prince of Wales (Later to be known as King George V)

The Persian Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911)

Parliament in 1906.

The Persian Constitutional Revolution occurred between 1905-1911. The end result of this revolution led to the establishment of a parliament (known as “Majlis”) in Persia during the Qajar dynasty. The establishment of the constitution created institutions to put a check on the Qajar dynast and created a constitutional monarchy framework in the Persian government.

“This revolution brought about a transference of political powers; but unlike the French Revolution of 1789 and the Russian of 1917, it made no fundamental alteration in the social or economic structure. Yet, with all of its limitations, it marked at event of importance: a successful assertion by Persians against internal and external power.”

The reason the date for this revolution is not on a single day is because there was a back and forth in the power struggle between proponents of a constitution and the Qajar dynasty. Eventually enough instability led to the Pahlavi dynasty when Reza Khan Pahlavi took the thrown of the country in 1925.

“What were the conditions that precipitated revolt? The sufferings of the masses had little to do with it. No general intellectual ferment was occurring. No social theory or political philosophy captured the minds of these men. No passion for abstract liberty-not even any general conception of freedom-aroused emotional enthusiasm. Ideas and ideals of democracy had little currency. Yet the revolutionary movement did reflect increasing enlightenment, a growing sense of injury in the upper and middle classes, a stirring of nationalistic feeling, and in a small group a genuine desire for progress. Rivalry between Britain and Russia played an important part. The British were supposed to resent the friendliness of the Shahs toward Russia and to feel that British interests would be promoted by a constitutional regime.”

Rule of Reza Shah Pahlavi (1925 – 1941)

Reza Shah Pahlavi

“In 1921 Reza Khan Pahlevi, son of Mazanderan peasants and colonel of a brigade that had been organized by the Russians, marched into Teheran, set up a new prime minister, and made himself Minister of War and Commander in Chief of the Army. He was soon recognized to be permanent in these positions, and, by reason of his military power and personal qualities, to be a potential dictator.” He eventually came to be the next dictator of Persia and ended the Qajar dynasty on 15th of December, 1925.

“He was a creature of primitive instincts, undisciplined by education or experience, surrounded by servile flatterers, advised by the timid and the selfish. He was sincerely and deeply moved by the sorry condition of his country, conscious of his own strength, and supremely self-confident…He was in some respects a great man, in sum of his qualities and achievements, and extraordinary phenomenon. Big, erect, roughhewn, eagle-beaked, he remained to the end a soldier. Endowed with enormous energy, he worked without end or fatigue and drove others mercilessly. In the ancient way or oriental monarchs, he attended personally to the affairs of the state from the highest policy to the minutest detail. In the later years of his reign he seems to have become insane with power. The story is told that he wished to plant some trees in a certain spot. His forestry expert said: ‘Your Majesty, they will not grow there.’ The reply was: ‘They will if I order them to.’…Brutality and greed, already well marked among his character, grew to dominate his behavior. In keeping with his nature and in the tradition of Persian despots, as well as other dictators, he took fear as his primary means of governing.”

Millspaugh recalls his view on Reza Shah, “When I knew Reza, it seemed to me that he was unmoral, rather than immoral. It is proverbial in Persia that honest men are lazy, and active men are dishonest, and Reza Shah doubtless prized activity too highly; but not doubt he found the dishonest more congenial, more willing to be his tools, and more satisfactory from the standpoint of monetary returns. In any event, as time passed he put aside his more or less decent counselors and surrounded himself with the worst elements of the empire. These he made his accomplices. To these he gave privileges and favors. With amazing thoroughness, he rewarded vice and punished virtue. At the same time, he presented to his impressionable people a personal example of colossal corruption.”

Millspaugh goes on to write, “Persian rulers and satraps late in the nineteenth century indulged in torture and in cruel and inhuman punishments, and in this respect Reza Shah proved no exception. During my first Mission, someone gave me a photograph of a man buried alive up to his chin…I was informed on my return to Persia that he had imprisoned thousands and killed hundreds, some of the latter by his own hand. Several prominent men, I was told, were poisoned in prison; for example, Firouz, former Minister of Finance; Teymour Tash, once the trusted Minister of the Court; and Sardar Assad, a chief of the Bakhtiari who at one time had been Minister of War. Davar, already referred to as an exceptionally able official, committed suicide. Kheykosrow Shahrock, Parsee deputy, respected business man, and a former friend of the American Mission, was murdered by air injection. Religious sanctity or sanctuaries did not deter the despot. He desecrated shrines and beat up and killed holy men. Fear settled upon the people. No one knew whom to trust; and none dared to protest or criticize. Except at the very beginning no one seems to have attempted to assassinate the Shah. He himself, it is said, believed that he was destined to live long.” I find it fascinating to hear of the murder of Kheykosrow Shahrock in this book, whom appears to be a prominent Zoroastrian and played a critical role in transforming the Islamic Calendar used in Iran to an Iranian Calendar that follows the sun cycles as observed by the Zoroastrian community as opposed to the Moon cycles observed by Arabic-Islamic Calendars. I cannot confirm anywhere on the internet how he died, so this may just have been a rumor and it is not clear if it is in anyway connected to Reza Shah.

Kheykosrow Shahrock

Millspaugh recalls a humorous event in which the ego of Reza Shah led to the Persian government purchasing an American school in Maryland, “At one time, he angrily recalled his Minister at Washington on the ground that worthy, while motoring through Maryland, had been insulted by a constable who seems to have been more familiar with traffic rules than with diplomatic immunity. The Persian government purchased the American school and college, founded and ably conducted by the Presbyterian missionaries.” Reza Shah did not have a very high opinion of foreigners, “Reza’s dislike of foreigners went to such extremes that he forbade his people to visit the embassies and legations and practically terminated social contacts between Persians and the foreign diplomats. The government continued to employ experts from other countries, chiefly from Germany and Switzerland, but only for factory management and technical services and never with authority.”

Reza Shah Pahlavi alongside Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Among the major social changes Reza Shah Pahlavi Introduced:

- Compulsory military service

- Removal of veils for women

- Granting women to University, Government Offices, and other Social Functions

- Sending many youths to foreign universities in Europe

- Large scale industrialization and construction projects

“During the regime of Reza Shah, hundreds of young Persians had been educated in Europe and at home.” My grandfather was among these people, whom studied economics in Great Britain. “A large proportion of these had found employment in the dictator-king’s expanding administrations. Reza probably did not know the defects of his bureaucracy; the bureaucrats themselves either did not know or did not want others to know; and few outsiders could learn the truth.”

On the building of infrastructure Millspaugh writes, “How he could have done so much building of such variety in so short a time must remain a mystery. I have already mentioned the railroad-its tunnels, bridges, and stone buttresses were alone wonders-and the factories, roads, streets, and hospitals. The railroad station at Teheran would hardly compare with the Grand Central or Pennsylvania at New York or the Union Station at Washington, but it is as ample and impressive as, for example, the depot at Kansas City. The Shah largely replaced the ancient, crude, caravansari-like government buildings with modern, spacious, and for the most part well-planned structures. He gave the Persian National Bank an appropriately impressive and well-adapted edifice. He moved the Ministry of Foreign Affairs into palatial quarters. He made Luxurious provision for the Officers’ Club; and he erected a massive stadium for his revived athleticism. He housed the university in a group of attractive buildings. He put up hotels at the foot of the Elburz near Teheran, at three or four spots in the mountains, and on the Caspian shore. In some of the small towns and villages he arranged shopping centers, and here and there in rural neighborhoods supplied the peasants with improved standardized houses. He created at Fariman in Khorassan a model town complete with factories, shops, and stores. At the time of his abdication, buildings of all sorts at Teheran and through the North were in various stages of construction-offices for government departments, branch railroad lines, a building for the insurance company, hotels, and casinos.” But not all of these development projects were productive, indeed many were wasteful. An example of this is in Tehran where, “…the Shah built an opera house (where there was no opera), and a government-owned department store (in a land of bazaars and small shops)…He also swept clear a block or two for a stock exchange, and is said to have specified that it must be bigger than the one in New York. Fortunately, it was not constructed.”

“Reza Shah made some monumental additions to the country’s transportation facilities. He completed the Trans-Persian Railway, one of the world’s outstanding engineering feats, and partly completed three ambitious branch lines. He built new roads, improved old ones, and started paving. He widened the main streets in most of the cities, tore down walls, laid out boulevards, opened vistas. Automobile and motors trucks multiplied. Commercial truck and bus services started. Filling stations appeared. Teheran, half dark at the time of my Mission with limping electric power and with houses mostly dependent on kerosene lamps and candles, burst into light at the touch of its dictatorial Aladdin.”

Turntable in Ahwaz

Trans-Persian Railway Constructed going up Alborz Mountain

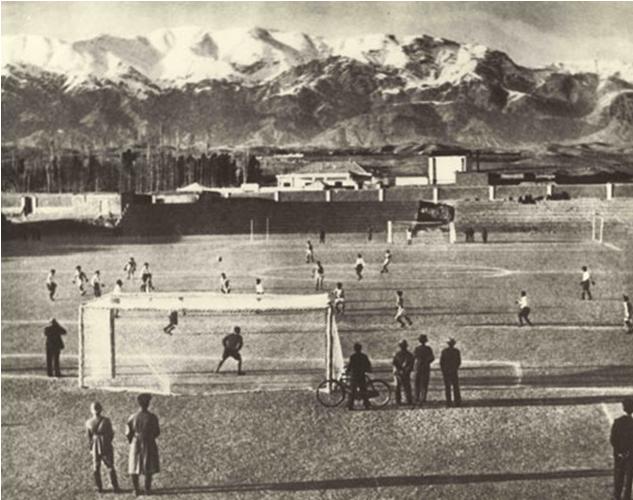

Soccer match at Amjadiyeh Sports Stadium, circa 1935-1936

“Sports flourished at the command of the Shah and with the financial assistance of the government…the conservative Moslem clergy had been stripped of their power and prestige. Religious observance declined…Cinemas, restaurants, night clubs, and dancing gave lightness and atmosphere to a once drab capital. Camels and donkeys, still useful means of transport, fell under imperial disfavor, because they were primitive.” “While the Shah was working these expensive and dubious miracles, he amassed for himself a substantial fortune.”

Nasser Khosrow Street, Tehran 1920s

Although undoubtedly there were some positive social changes caused by Reza Shah Pahlavi, there were still many painful social problems that remained or became exacerbated. “The Shah’s taxation policy was highly regressive, raising the cost of living and bearing heavily on the poor…While his activities enriched a new class of ‘capitalists’ – merchants, monopolists, contractors, and politician-favorites – inflation, heavy taxation, and other measures lowered the standard of living of the masses.”

Invasion and Forced Abdication of Reza Shah Pahlavi (1941)

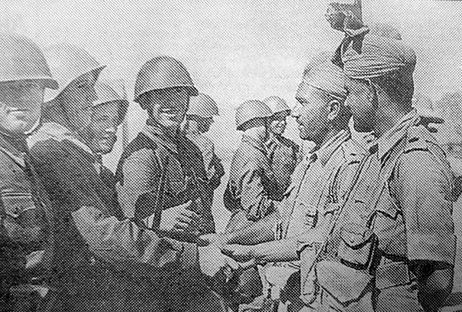

Soviet and British Indian Soldiers meet in Tehran in Late August 1941

By 1940 the British and Russians had lost confidence in Persia remaining a neutral power. “Reza Shah may have demonstrated that a strong Persian government could keep Russia at bay; but to all intents and purposes he handed Persia over to Hitler.” “In 1940-41, Germany had taken first place in Persia’s foreign trade…when in June 1941 the Nazis invaded Russia, their activity in Persia intensified.”

On June 22, 1941 Nazi Germany decided to break its agreement with Russia and invade the territory of Russia. Shortly afterward in August of 1941 a Soviet army from the north and a British army from the south successfully invaded Persia and met at Tehran to ensure that the country did not fall into the hands of Nazi Germany and also due to the strategic importance of its resources for the war efforts. “…the Allies could not permit Persia, at the backdoor of hard-pressed Russia, to be occupied by the Nazis or used as a base for activities either among the Persian tribesmen or in Afghanistan and India. The British and Soviets, therefore, demanded that the Persian government dismiss its Nazi employees and arrest the Nazi agents in the country. The Shah procrastinated; Britain and Russia presented an ultimatum; and failing to receive satisfaction, they invaded the country in August 1941, a British force from the South, a Soviet from the North.”

“When Great Britain and Russia invaded Persia in 1941, the country might justly have been treated as an enemy, for to all intents and purposes the government of the time had delivered itself to Hitler…the Persians, so far as I could see, never became unfriendly to Nazi Germany with any strong feeling or unanimity, nor did they become generally and enthusiastically pro-Ally. Their historic distrust and fear of the British or the Russians or both precluded any clear recognition of a common cause or genuine spirit of collaboration.

Signed Photograph of Adolf Hitler for Reza Shah Pahlavi in Original Frame with the Swastika and Adolf Hitler's (AH) Sign - Sahebgharanie Palace - Niavaran Palace Complex. The text below the photograph: His Imperial Majesty - Reza Shah Pahlavi - Shahanshah of Iran - With the Best Wishes - Berlin 12 March 1936 - The signature of Adolf Hitler

“At first, Reza wanted to offer resistance and a few shots were fired, but his Army collapsed ignominiously. It appears that the officers quite promptly turned tail and ran…The two Allied forces met in Teheran. The Soviet Ambassador and the British Minister demanded the Shah’s abdication. Reza necessarily agreed…The British escorted the ex-Shah with two of his sons and a few aides and servants to a southern port. Put on a ship there, he apparently believed that India was to be his place of exile. Informed at Karachi that he was being taken to South Africa, he lost his cheerfulness, withdrew from his entourage, and brooded alone and long. Of his subsequent lift and thoughts, his former subjects learned little. He died at Johannesburg in July 1944.”

“Great Britain and the Soviet Union concluded a Tri-Partite Treaty of Alliance with Persia on January 29, 1942. The two powers ‘jointly and severally’ undertook to ‘respect the territorial integrity, the sovereignty and the political independence’ of Persia. The latter gave to the Allied powers the use of all means of communication throughout the country including railways, roads, ports and telephone and telegraph lines…In Article V Great Britain and Russia promised to withdraw their forces no later than six months after the end of the war with Germany and her associates…the Persian munitions factories and a canning factory turned to the service of the Red Army; and the British leased an airplane assembly plant.”

With the fall of Reza Shah Pahlavi there was a resurgence of hope that a new constitutional leadership would fix the problems of Iran, and another American Mission was requested. “Constitutional government, restored, betrayed its impotency; but in the reaction from Pahlevi’s tyranny the dream of 1906 seemed to have another chance for fulfillment.”

Millspaugh suggests that the present of foreign military presence was actually a stabilizing factor to Persia, “…the presence of Allied armies in the country served as a temporary stabilizing factor of great importance. Had it not been for the presence of these armies, it is difficult to see how Persia could have escaped widespread disorder, a breakdown of organized government, and probably a period of virtual anarchy.”

Despite calling him “in some respects a Great Man”, Millspaugh was quite critical of Reza Shah Pahlevi and suggested his forced removal was a blessing for the country, “From 1926 to 1941 an irresponsible despot ruled the land. At the end of that regime, foreign armies occupied the country, while the Persian government lapsed into hopeless ineptitude…Removal of Reza Shah Pahlevi was alone of incalculable value, and for that service his former subjects should be grateful…the ex-Shah’s despotism, if it had not been cut short by the Allied occupation, would almost certainly have been followed either by absolute monarchy or by civil war. For Reza Shah destroyed in the souls of his subjects the qualities that fit men for self-government; and he apparently destroyed even the capacity of this own people to produce dictators.”

Rule of Shah Mohammed (1941 – 1979)

A Young Mohammed Ali Pahlevi with his Father, Reza Shah Pahlevi

“Reza abdicated in favor of his twenty-two year old son, Mohammed Ali Pahlevi, who promised to be a constitutional king.”

Millspaugh did not have too much to say about the young Mohammed Reza Shah. He left Persia before he really started to use his power to steer to country, but he did write the following about him, “At the top of this rotten and tottering governmental structure sites a young and perplexed Shah, flanked on the one side by an over-polished court and on the other by a corrupt and incompetent military clique, predisposed to dictatorship. He admits that Persia is not ready for democracy and he has never lost his admiration for his father…How he will use the considerable influence that he possesses and what will eventually come to him remains to be seen.”

History has shown that ultimately the rein of Mohammed Reza Shah came to an end with the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Theoretically the Islamic Revolution sought an end to dictatorship but it is hard not to call post-1979 Iran a non-dictatorship. The country to this day appears to be unable to sustain a capable democracy, or government.

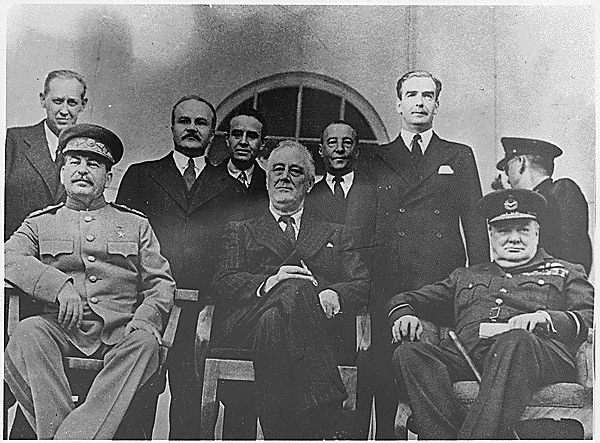

Tehran Conference 1943

Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill at the Tehran Conference 1943

Between November 28 and December 1, 1943, Tehran hosted a conference between the leaders of the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States of America. The conference was intended to provide an opportunity for the powers to coordinate their efforts against Nazi Germany and Japan. However, Millspaugh writes, “Observers at Teheran could see that the three powers were not of one mind and did not fully trust one another, that Russians acted on way and British another, while Americans had a third type of behavior.”

The conference made an impression on the Persian population, “So far as the Persians could see, however, the American government, as well as the British, feared the Russians and exercised slight influence over Russian actions. The Teheran Conference and the Declaration that issued from it flattered the Persians and created a better impression regarding Allied unity and American influence. This impression, however, was temporary, for after the Conference the Allies showed no perceptible change in their individual conduct or in their relations with one another; and in the fall of 1944 they engaged in a competition for oil concessions that was more or less discreditable to all of them.” Ultimately Millspaugh writes, “It became quite evident in this corner of the world that the three powers did not achieve a common understanding…”

The American Missions (1911, 1922-1927, 1942-1945)

“Persian leaders recognized that, under the circumstances of the time, they could not place the government on a sound financial basis without the employment of foreigners. They also realized that unless they ‘put their own house in order’ their weakness and insolvency would keep them, as in the past, at the mercy of the British and Russians.” “…the Persian government has on three occasions called on America for help; and, beginning in 1911, three American financial missions have responded to the call. These missions, along with other Americans who have served in Persian administration, have played an extensive and significant role in the modern history of the country.”

Goals of the Missions:

- To bring about national unity

- To ensure order and security

- To establish efficient and honest administration

- To place public finance on a sound basis

- To promote the prosperity of the masses

- To provide for health, education and social welfare

- To introduce the essentials of democratic government

Tasks of the Missions:

- Controlling financial operations

- Planning and construction of the Trans-Persian railroad

- Supervising highway construction

- Engineering irrigation projects

- Managing of the public domains

- Promoting agriculture

- Serving as experts in the Teheran municipality

- Directing the collection of grain and the distribution of bread

- Conducting an emergency program of rationing and price stabilization

- Making educational surveys

- Assisting in Public Health Administration

- Organizing the gendarmerie and police

- Advising the Army

“The Persians knew likewise that financial reform was a condition precedent to internal development and progress. Dissatisfaction with the French and Belgians and the undesirability of engaging British or Russians left America the appropriate, if not the only, quarter in which to seek administrative help.”

The First American Mission (1911)

W. Morgan Shuster

After the constitutional revolution in Persia, the Persian government sought foreign assistance to establish a western-oriented, democratic civil society. “President Taft suggested W. Morgan Shuster for the Persian job” and Shuster was appointed by the 2nd parliament (Majlis) to help the country’s financial position. However, “Shuster’s position and his program rested on the assumption of Persian independence.”

President Howard Taft, U.S. President (1909-1913)

“Shuster found that the conditions were so disorderly and contempt for the government so widespread that he required a gendarmerie under his own orders to ensure the collection of taxes. Having no one on his staff to organize this force, and as time pressed, he asked the British to lend an army officer for this task. They did so.”

However, the Russians refused to allow this British officer in the northern territories of Persia making the collection of taxes in the north impossible. After nine months from his arrival the Russians demanded his removal and a weak Persian government was too divided to resist. Shuster had no option but to leave, this is how the first American mission ended. Shuster later wrote a book about his experience titled, “The Strangling of Persia”.

The Second American Mission (1922-1927)

When Millspaugh entered Persia in 1922 he found the Persian treasury empty and the administration in charge of the country’s finances was in complete chaos. Perhaps his most pressing duty was to properly implement a national tax program that could be enforced. Millspaugh writes, “From the beginning, we met resistance from the landlords, particularly the grandees, who for years had escaped payment of taxes.” Due to his efforts the government was able to restore income via taxation, however for his efforts he received the nickname “Dr. Poul Nist”, which translates to Dr. There is no Money. Millspaugh writes, “The government with our assistance balanced the budget, started payment of claims, and provided for the financing of new constructive undertakings.”

“The Parliament enacted a surtax on sugar and tea, which produced the funds that built the Trans-Persian Railway. American engineers, employed by the government on my suggestion, made the surveys and started construction. Another American engineer, similarly employed, directed the building and maintenance of highways.”

“Had it not been for the beginnings of large-scale looting by Reza Khan and his Army, popular confidence in the government, indispensable to national unity, might have been gradually created in the minds of the people.”

“It was well known also that Reza helped himself liberally to army funds and used the proceeds for personal purposes. He was already receiving ‘gifts’ of villages, ‘gifts’ proffered under duress or from fear. At the time he became Shah, his amazing greed had already made him wealthy.”

Millspaugh wrote a book about his experiences in this first mission titled, “The American Task in Persia.”

The Third American Mission (1942-1945)

This book principally covers Millspaugh’s experiences during the third American mission. Once again, after facing a challenging financial situation the Persian government sought American support and had a relatively positive opinion of Millspaugh’s work to restore confidence in the government’s finances in the 20s. “…the Persian Parliament approved a law embodying the terms of my contract on November 12, 1942. The contract was for a period of five years; and, from my point of view, the primary purpose of this Mission, like that of past undertakings, was to assist Persia to solve its normal longstanding problem, as much as conditions might permit during the postwar period. Although the Atlantic Charter had been proclaimed more than a year before, the Department had apparently given little thought to the postwar period, so far as the fundamentals of the Persian problem were concerned, or with respect to American responsibilities in the Middle East for the maintenance of world peace. I was informed, however, that the United States after the war was to play a large role in that region with respect to oil, commerce, and air transport, and that a big program was underway.”

“The American tradition in Persia had been built up by the two previous Missions, and it contrasted sharply with the impressions and recollections left in the country by men of other nationalities. Americans had worked for Persia single-mindedly, impartially, and exclusively, with no political or commercial strings attached to them. Their job, as they saw it, meant much, not only to the country that employed them, but also to their own reputations and future prospects.”

“Most important of all, however, the maintenance of the Mission with no compromise or retreat would have had symbolic influence over both Persians and Russians. It would have demonstrated, as nothing else could, the purpose of the United States to hold its ground and play a strong and stabilizing role in the Middle East.”

According to Millspaugh, “Conditions in Persia and the job that circumstances compelled us to undertake called for a much larger mission than had been originally authorized…At the end of our first fiscal year, the Mission had grown from 8 to 41 men. We now had members of the Mission in charge at Kermanshah in the West and at Isfahan, Ahwaz, Shiraz, and Kerman in the South; but meeting Russian obstruction, we had been unable to station men also at Meshed and Rasht in the North.”

It was a constant challenge to deal with reputational and political attacks and to be able to hire and keep a quality work force. With regards to hiring Persians, Millspaugh writes, “Most of the old, experienced men and many of the young and educated proved in practice too proud to work in positions that we could assign to them.” With regards to the challenges of hiring Americans, he writes “Most of the men accepted as a matter of course the challenging difficulties under which they had to work – demoralization, dishonesty, obstruction, and intrigue among the Persians, the use of the two languages, insufficient office equipment, lack of stenographic assistance, and the almost insufferable delays in getting things done. The magnitude and complexity of the Mission’s task, together with the attacks and criticisms that were aimed at us, bewildered many at the start, confused some, and shook the confidence of a few.” The health challenges were not few. “The intestinal parasites and microbes that abound in the uncleanliness of the country appear to be mobilized for the prompt infestation of newly arrived foreigners, especially Americans.” Millspaugh contracted amoebic dysentery and twice put him into the hospital for a total period of seven weeks. There were many examples of employees being forced to be let go, “Another well-qualified recruit after three weeks’ work went back to the United States with a diagnosis of high blood pressure…Another man after several weeks of dysentery developed heart disease…Thugs attached one of the Mission as he walked along a Teheran street at night. One of our America provincial directors told me that he had been shot at three times. Another, riding with his wife and two children, was attacked by bandits. A number of our Persian finance employees were murdered.” Some of these attacks may have been a result of different rumors being spread around the country. “The papers informed their readers that Americans were spending their time and money at night clubs; and many articles concerned alleged American involvements with lady stenographers and prostitutes.”

Milsspaugh desired to reduce the expenses and size of the army but was never able to do so. “I desired to force a reduction in the Army, first, to balance the budget and pay the debt, and, second, to facilitate the financing of agricultural development and social services.” He was however succesfull in introducing rent control, “After many conferences with the Minister of Justice, we succeeded in getting rent control under way.”

“Persia had three banking institutions owned and controlled by the government, a National Bank, an Agricultural and Industrial Bank, and a Mortgage Bank…In addition, there was the Army’s wild-cat enterprise, the Bank Sepah…From the start, I took steps, with some effect, to strengthen these boards and free them of political connections; but found no favorable opportunity to do anything about Bank Sepah.”

Ultimately there was too much obstruction to have a fruitful operation, and likely not enough time and commitment from the U.S. Government. Millspaugh writes, “The existence of world war, the presence of Allied armies, the menace of seemingly runaway inflation, the threat of famine, the insufficiency of the Mission at the start, and the slowness with which it grew to adequate size, in addition to innumerable lesser difficulties, including Russian opposition and obstruction, made it impossible for us to produce spectacular results or even for several months to offer to the simple-minded deputies and public any convincing demonstration of usefulness or progress. Persians expected sudden public miracles or substantial private benefits. We could neither overawe with miracles nor bribe with benefits…the Mission had been administratively handicapped and retarded by the obstruction, the nonco-operation, and the unfair and destructive criticisms of the Persians themselves, as well as by the difficulties that the Soviets had created in the North.”

However, Millspaugh does lay some of the blame on himself and the U.S. government, “Our failures in Persia may be explained by poor organization; by defective or inadequate informational services; by lack of co-ordination among the departments in Washington; by disagreements among officials of the State Department, causing confusion of purpose, delays, compromises, or total paralysis: by personal jealousies and intrigues; and by incapacity or laziness.”

With regards to support that mission received, Millspaugh writes, “In spite of the opposition just described, it was certain that a vast majority of Persian people preserved toward the Mission and myself feelings of real friendliness and confidence, wanted the Mission to stay, and had no particular objection to its authority or its setup. Except for the complaints and intrigues of the rich factory-owners in Isfahan and a few demonstrations instigated by the Soviets in the North, no opposition of any more than routine importance or normal nature appeared in the provinces.” Millspaugh continues, “Those of our friends who could have made themselves heard and possessed intelligence, honesty, and patriotism lacked conviction, courage, energy, and organization. They were suffering from the ancient Persian weaknesses and from the effects of dictatorship and its aftermath quite as much as our enemies, though in a somewhat different way.” I find it fascinating that he labels a lacking of conviction, courage, energy and organization as “Ancient Persian Weaknesses”. He may be suggesting that many generations of harsh dictatorship rule have weeded out these qualities among the population.

There were many signs of difficulties in dealing with the U.S. Government. Millspaugh writes, “The Department of State certainly suffered from an utterly inadequate intelligence service and equally from an inability to digest, evaluate, and analyze the information that it received…In short, our democracy may have been again demonstrating its inability to cope with the strategy of dictatorial power politics.” He continues, “When the Department finally ‘insisted’ that I take steps to improve the administrative and personnel side of the Mission, I pointed out that I had been taking such steps from the beginning and in a letter dated March 4, 1944, I asked the Department to inform me what steps, in addition to those already taken, it would insist that I take. I received no reply.”

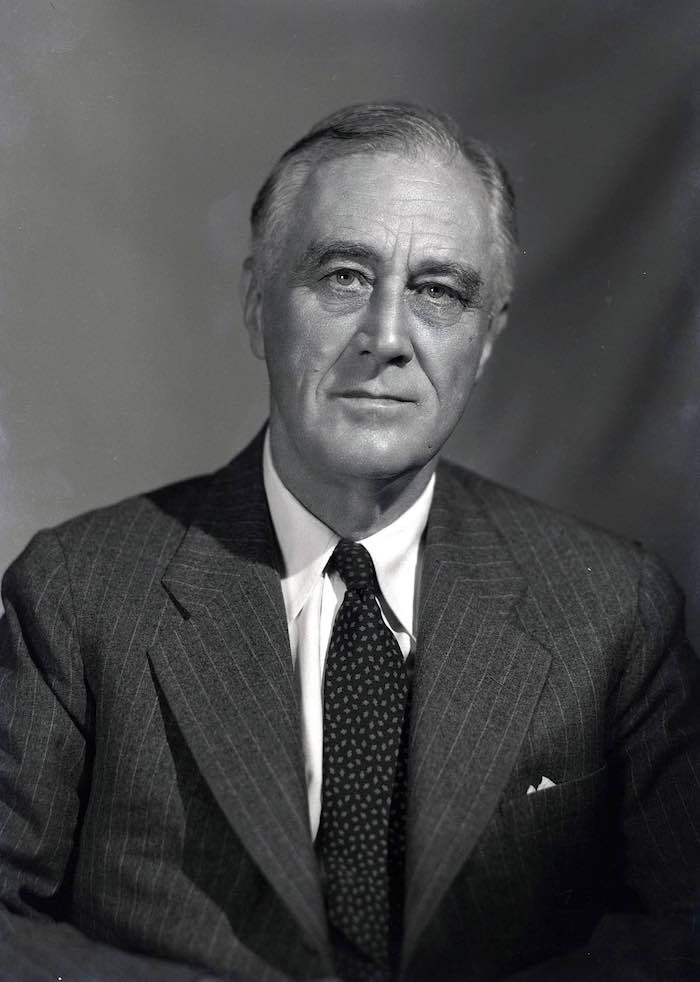

Franklin D. Roosevelt, U.S. President from 1933-1945

“When the President asked me to tell him about our work, I took occasion to explain the plight of Persia and suggested that to do the job would require a more comprehensive jurisdiction, an assured period of at least twenty years, and the full support of the United States government. I gave Mr. Roosevelt a brief memorandum on December 1, 1943, and wrote a letter on January 11, 1944 to Harry Hopkins, who had asked the President to see me and had been present at the interview.”

“In the letter of Jan. 11, 1944, I included the following statement: “The history of most undertakings of this kind in Iran is that they come to an untimely end before any lasting results have been accomplished, and, with the departure of the American administrators, the country again lapses into disorganization, or, as after our previous service here, it turns to dictatorship. You may be assured that, during the short time allotted to use, we can not in injustice to the Iranian people who expect so much from us, to leave before substantial and durable results have been achieved. Twenty years, I think, is the minimum time required...I received no reply to either of them or comment upon them.”

“While the Department of State talked about a ‘program’ it actually had none. It had sent men to Persia without a plan and in accordance with no known principle of organization. My idea was that we should strike while the iron was hot and establish the foundation of the larger postwar effort while circumstances remained favorable.”

“In the case of Persia, it is the fluid human principles, not the frozen legal ones, that need to be applied; and it is the people, not the governing class, to whom help must be given. Yet, if I have interpreted American policy in Persia correctly, we believe that we must deal with the government, no matter how grossly it misrepresents the people or how much it disregards and violates human rights. This ‘respect’ for ‘sovereign’ rights, though not applied consistently, led us to play along with the privileged, the racketeers, and the majority opinion. Our diplomatic procedure played into the hands of a governing class, which is cordially hated by the masses and contrary, which in no way represents the people, which is probably the most corrupt in the world, and which is undoubtedly as selfish, shortsighted, and irresponsible as any since the French Revolution.”

Despite the struggles, Millspaugh believed that the American mission in Iran were the most productive efforts to bring stability to the country, “Of all the devices tried in Persia, the three American missions made the best showing, equipped as they were with authority and unity and, in the latter two instances, with a contractually allotted period of time in which to work.”

Once Millspaugh decided that the mission could not continue and it was time to leave he made sure not to leave at a time of crisis like last time to hurt American reputation and prestige. “…I had informed the Department of State of my personal desire to leave the job; and my hope was that the American government would take steps to maintain the continuity and character of the Mission and as an essential means to this end would give me support until I could step out without damage to the Mission, to the progress of its work, or to American Prestige. During the debate in the Majlis on the Full Powers Law, I might have submitted a resignation as I had at previous times of crisis in October 1943 and June 1944. I did not do so, because I knew that such action would merely play into the hands of the opposition…”

Millspaugh left Persia on February 28, 1945, never to return.

In his concluding remarks he writes, “…we have less now in Persia that we had in 1943. The American Army and the Financial Mission are gone. The State Department’s failures in 1943, 1944, and 1945 to seize opportunities and its lack of perception at critical times and on strategic issues needlessly sacrificed diplomatic advantages and exchanged a strong position for a weak one. By our strait-laced deference to Persian sovereignty we did not help our own hands, prevented ourselves from meeting Russia on realistic ground, and permitted the Soviets to continue their undercover manipulations. Our show of vigorous leadership in the United Nations Security Council in March-April 1946 ended with an act of appeasement. In effect we endorsed Persia’s surrender to the Soviets.”

Author’s Views on Persia and Persians

Tehran, 1930

Arthur Millspaugh had quite a lot to say about his impression on Persian people. He was quite disappointed about the failure of his attempt to help modernize the country and prevent a reversion to dictatorship so it is very possible that he just had to let some steam out, but I do feel that much of his criticisms are at least to some degree rooted in truths. He also makes an important point here, “To understand Persia’s internal political situation, it is necessary to state some unpleasant and discouraging facts…We can help Persia only when we know her character, her difficulties, and her needs…The mind and character of the people determine the main features of their political life and the course of their political evolution, while their government, or misgovernment, reflects the general mental development and the emotional drives of the people.”

First with regards to nationalism he has the following to say, “…Persian nationalism is displayed, not felt. It is displayed as a political weapon, as an expression of antiforeign prejudice, as a psychological defensive mechanism, and as a reflection of individual egotisms. Nationalism, in the form that Persian extremists express it, is a disease not a sign of health and growth; it is a reactionary and crippling, not a progressive and liberating, influence.”

With regards to how the culture deals with social status and ranking he had the following thoughts, “In the Orient, governments as well as individuals must build and maintain their prestige. The winning of friendship, the cementing of relations, the exercise of leadership, the development of trade relations, the acquisition of economic concessions, and the general execution of policies and accomplishment of purposes, all depend on prestige. In the case of a government the most important ingredient of prestige is power. Power is most convincingly demonstrated by adequate and available military forces, by a firm insistence on respect, by complete consistency, by never taking positions that can not be maintained, and by never retreating from a position once taken…in Persia when you lose power you lose prestige, and when you have lost prestige, nothing can be gained by hanging around and hoping.”

Hookah and Tea 1935, by Wolfgang Wiggers

It became very clear early on for Millspaugh that working with Persians was very different than working with Americans. He writes, “Work in the Orient makes peculiar and excessive demands on the one’s tactfulness because of the emphasis on formalities and the sensitiveness and pride of the people…” He continues, “Out of their long history and their more recent vicissitudes, Persians have taken on certain emotional characteristics associated with feelings of inferiority and insecurity, accompanied by compensatory and defensive urges, and complicated by shock and demoralization. The Persian of today exhibits a quite definite pattern of feelings and behavior, very different from the emotional makeup of the westerner…” “…in this regime of personal authority, personal caprice, and personal insecurity, men had to learn well the way to win favor and climb over others…fluent flattery, expert bribe-giving and bribe-taking, subtle intrigue, and artful evasion. Sensitiveness and pride grew to an acute point. That intangible thing, called prestige or ‘face’, became everywhere except at the hopeless bottom of society the most sought and most valued personal possession.” “It was quite evident that liars were not objected to; but we were soon led to a more amazing observation, that people who were not habitual or professional liars themselves actually seemed to prefer lies to the truth and gave more value and currency to falsehoods than to facts.”

Village Elders 1935, by Wolfgang Wiggers

With regards to the psychology of the Persian, Millspaugh writes, “The Persian is quick and agile of mind, a good conversationalist, responsive and witty, and in his more serious moments or to escape reality he turns to the reflective exercises – philosophy, poetry, and the arts. He is not a man of reason. He falls short of intellectual maturity. He generally and substantially lacks the apparatus that more advanced peoples developed to solve problems and engineer progress.” He continues, “A keen American, who was long in a peculiarly favorable position to observe the mentality of this people, remarked to me that Persians were ‘children,’ with a mental age of about eleven years. I am sure he did not mean to say that Persians were mentally deficient; he was referring, rather, to their undeveloped and unused reasoning faculties; and I imagine he had in mind their emotional as well as their mental age…Basically insecure, Persians have sought and are still seeking escape from reality…The environment and circumstances that produced political and economic frustration may have impelled an unconscious withdrawal from reality. Many took refuge in the aspirations and contemplations of religion, philosophy, and poetry.”

I found this to be a fascinating quote by Millspaugh, “With respect to intellectual capacity, Persians are probably equal to any other people and superior to some; but Persian intelligence is limited by experience and habit and is emotionally inhibited.” I am not sure what he means by “superior to some”, but it is interesting to see this language of generalized comparisons of populations. Of course, this was popular in the middle 20th century, but in the modern era is quite politically incorrect. In many ways Millspaugh felt the Persians were hoping for a savior, almost a religious figure to better their lives, “One may guess that this still primitive people have unconsciously yearned for a Great Father, in the form of a dictatorial Persian or a benevolent American, who would extend protection and work miracles to the vicarious satisfaction of the Persians and without calling for initiative or courage on their part.

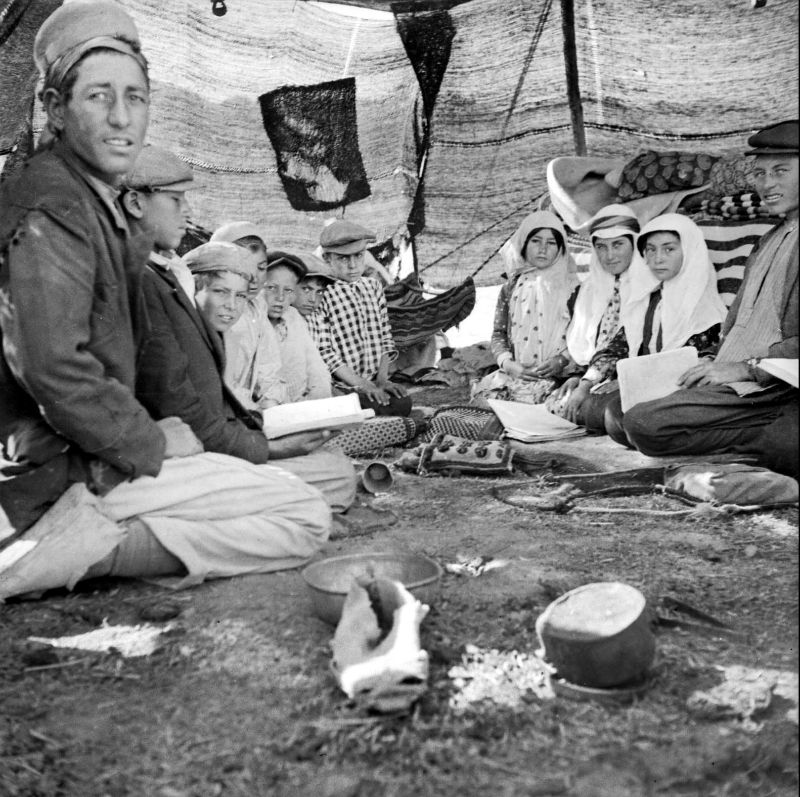

Village Children Studying 1935, by Wolfgang Wiggers

In general, Millspaugh saw Persians handicapped primarily by some sort of psychological or emotional hinderance, he writes, “We should approach the educational part of the program with the knowledge that the Persians need fundamental and many-sided rehabilitation. Education in this broadest possible sense is not just another item in the program: it is the central and vital feature and the final test of success. What the situation calls for primarily is not formal schooling. The prime need is for emotional adjustment and moral regeneration. The country requires a thorough physical and spiritual cleansing. He continues, “Their characteristics are not peculiar to them. Much the same mental, moral, and emotional conditions are found in different degrees in many countries and have probably appeared at some stage in the history of all.”

Camel Transportation 1935, by Wolfgang Wiggers

“Persians are not naturally a disorderly or a rebellious people. When they are well government, they can be easily governed. Contrary to the usual thinking of Persian politicians and bureaucrats, unity will come, not through centralization, but through decentralization, no through concentration of power and services at the capital, but through the spreading of authority and benefits to the frontiers.” “…the Persian became conspicuously individualistic, with mind centered on his own precarious living and scarcely conscious of any larger community except to distrust and fear it. His personal sociability and his attractive hospitality emphasize rather than qualify his essential individualism. His tendency toward association and co-operation with his fellows is strictly limited; and he lacks almost entirely any organizing skill, as well as ability to lead or to follow. Nevertheless, the family and the tribe hold Persians together with strong bonds, while village agriculture and village life represent primitive and local forms of community organization and co-operation.” “In this primitive society, the family was the natural primary unit, large, closely knit, with strong feelings of loyalty, honor, and mutual obligation.”

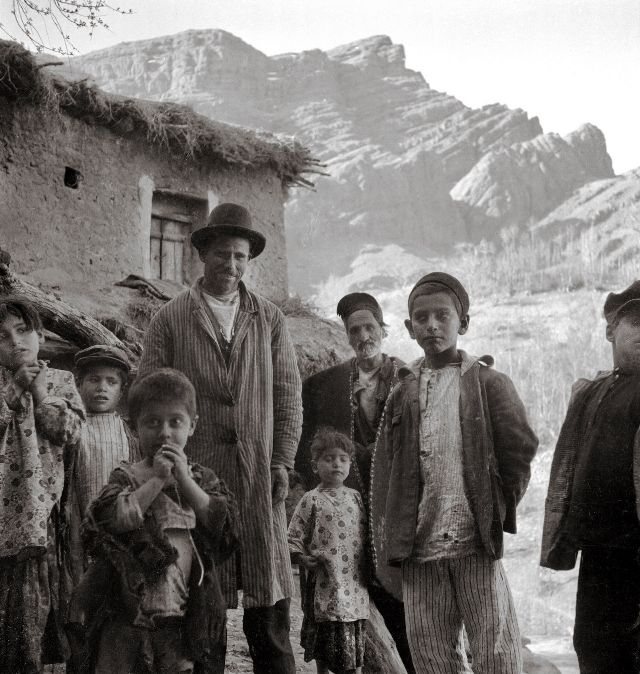

Remote Village in Persia, 1935, by Wolfgang Wiggers

With regards to social identity and unity Millspaugh writes, “The struggles and evolution in France and England, which resulted in the perfecting of national unity and the disappearance of feudalism, had no parallel in Persia. Semi-nomadic tribes, each a closely bound and largely autonomous group and each clannish, warlike, and given to banditry, made up from a fourth to a third of the population. The people as a whole became a striking mixture of races and types, including many racial and religious minorities, with divergent regional characteristics…As a race or a nationality, the Persians do not assimilate with other Middle Eastern people; and, while most are Moslems, they are somewhat apart by sectarian distinctions.” “Persia has not developed the basic essentials of democratic nationalism…Everywhere among the common people one can find distrust and hatred of government officials…Few see or feel their country as a whole or the people as one people.”

Just as in the past this quote is still true today, “Socially and economically the country is one of extremes. Wealth, like its accompanying political power, is concentrated in a few, while the mass of the population is sunk in a uniform and squalid poverty.”

Village Girl Getting Water 1935, by Wolfgang Wiggers

With regards to physical features Millspaugh writes, “Physically, Persians are tough and strong, particularly the tribesmen who are the best all-round stock in the country. The Persian laborer is famed for his endurance.” However, with regards to social values we have a less positive view, “One mental outlook that we associate with democracy seems to be almost totally lacking in Persia; namely, the conception of the dignity and worth of the individual human being.”

I will end this section with a positive quote, “No one can reside in the country without acquiring a lasting feeling of friendship and profound sympathy for the people.”

Remote Village 1935, by Wolfgang Wiggers

British Influence on Persia

For most of the modern era Persia was simply a pawn in the chest game of the great world powers, “Britain like Russia viewed Persia more or less as a pawn in the imperialistic game, and British policy concerned itself more directly with British economic interests than with the stability and progress of the country…Because of Persia’s geographical position, the country’s commercial opportunities, and the valuable British-owned oil fields at the head of the Persian Gulf, the British government has long and consistently looked upon Persia as an area closely related to the security and vital interests of Great Britain. The traditional policy has been to maintain Persia as a buffer state and as a means of checking Russian expansion southward, while taking all possible advantage of Persian markets and resources. It does not appear that the British government has ever entertained the purpose of destroying Persia’s territorial integrity.”

However, unlike the Russians, the British preferred the have the country be well governed, “The British want this country to be self-governed and also well-governed.” “Britain, like Czarist Russia, had its party and its protégés in Persia and, with more apparent activity than Russia, aimed to maintain in Teheran a government that was favorably disposed to Britain.”

Millspaugh was impressed by his experiences with British personnel in Persia, and had the following comments, “British representatives in Persia and in London who do the detailed work of executing policy are an extremely well-in-formed body of men.” “The British are handicapped by the fact that too frequently they give an impression of aloofness and carry a certain air of superiority; but, to the extent that my work has brought me into contact with them abroad, they have impressed me not only with their capacity, conscientiousness, and alertness as individuals, but also with their devotion, discipline, and unity as a group.” “It may be that British politics and the British civil service are on a higher intellectual plane than ours; and so Englishmen of good all-round intelligence, including those of cultural and literary bent, are more likely than Americans of similar quality to find their way into foreign service.” Millspaugh writes, “On the whole, the British intelligence service was the best in Persia.”

“While the British look forward to a self-governing and independent Persia, they naturally hope also for a friendly and a fair attitude on the part of the Persian government. The Soviets insist that the prime minister should be pro-Soviet; but the British, I think, are satisfied whenever he is a true nationalist and firmly impartial in foreign affairs.” “The British, on the other hand, would be content with equal economic opportunity; perhaps, as their critics might say, because they have already obtained all the special advantages that they want.”

However, the British had a difficult time like the Americans in dealing with the Russians, “Probably nowhere else in the world is feeling between the Russians and British so bitter, and probably nowhere else are charges and countercharges so freely flung about.”

Soviet Influence on Persia

According to Millspaugh the Soviets still viewed the world like a colonial power and were simply concerned about what territories were under their control as opposed to some sort of rules based world order that the United States was trying to create, “Some time soon, the American and British governments must decide whether the Soviet co-operation is attainable on terms compatible with the security of the West and a peaceful world order. Moscow appears already to have accepted the alternative, a division of the world into two power blocs. If the United States and Britain decide likewise and act in accordance with the decision, they must draw a line around what they consider to be the Soviet world and take their stand together in uncompromising defense of that line. Whether Persia should be on one side or the other or half on one side and half on the other must also be decided.” “They intend that Persia shall be a puppet state, and to accomplish that purpose they can be expected to use every method short of actually taking over the country, outraging American and British public opinion, or provoking war?” “They represented themselves as the champions of the masses against the landlords and the ‘capitalists’.

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, the two powers engaged themselves to respect the integrity and independence of Persia, but drew lines across the map of the country. “This convention did not ‘partition” Persian, but it set up spheres of influence which, in the natural course of events, would probably have led to a partitioning.”

Ultimately the Soviet policies in Persia were very similar to their behavior in other buffer states where they sought to extend their sphere of influence. I find it fascinating how similar these tactics are to today’s war events in Ukraine, it appears that Russia still has its Soviet culture, and perhaps it existed in Russia during pre-Soviet eras. “…it appears that what has taken place in Persia is of a piece with happenings in the Baltic states, eastern Europe, and Manchuria, and fits in with a picture, daily becoming clearer, that spreads into and over other regions.” “In Persia the Soviets acted strongly, with self confidence, a consciousness of power, and a clear conception of their postwar national requirements; while the British and Americans acted timidly, without clarity of purpose, postponing issues, and compromising principles.” “The Soviet program included much that was more substantial than mere agitation and propaganda or the stirring up of disorder. It included a systematic effort to treat the people of the North with kindliness and to safeguard their means of living. Whatever the end may be, we must concede to the Soviets a certain sound logic in their approach.” “In the pursuit of their expansionist purpose, the men of the Kremlin appear absolutely realistic and cold blooded. They do not want a big war, but they are ready to bluff and bully to the limit. They are anxious to get as much as they can while the getting is good.”

I think this great quote essentially describes everything you need to know of the Soviet Union and Russia of today, “…it disregards enlightened principles and marks a reversion to the sphere-of-influence doctrine and cynical imperialism of the past.” In short, they opt for a cynical world view and game theory out the world as a zero-sum competition to the death, it’s not hard to see why so many people do not appreciate that culture, especially the people living in it. It’s not to say there is no competition in life or that life is easy, but to give up on ideas like love, forgiveness, or empathy, sounds like spiritual suicide and will lead to a complex where you hate your own identity.

The Soviets were also keen to damage the American mission’s reputation, “Soviet attitude and actions not only delayed and damaged the Mission’s administrative work but also violated Persia’s sovereignty, Russia’s treaty obligations, and the assurances given in the Teheran Declaration.” “Without Soviet co-operation the Persian problem cannot be peacefully and constructively solved. Nor probably can any other problem of Europe or Asia.”

In describing the Russian psyche, Millspaugh writes, “The Soviet Union is more Asiatic than European, more Eastern than Western, and the Russian way of thinking and acting is in many respects quite like the Persian, though in other respects markedly different…“The Russian masses are possessed and moved by a real, almost religious love of country…Beneath and around this mass feeling one discerns the attitudes of a primitive peasant population, ignorant, accustomed to poverty and oppression, with almost no conception of the larger personal liberties or human rights, and devoid of any idea of political democracy. ..They love Mother Russia, they react to insecurity, and they respect power…Suspiciousness is one of the most noticeable and may be the most important of the characteristics of the Soviet governmental mind. With it, one encounters the habit of secrecy, the policy of seclusiveness, and the practice of keeping foreign reporters and observers out of the places where Soviet purposes are in operation. This baffling phenomenon may be attributed not only to suspiciousness but also to what Mrs. Roosevelt called an ‘inferiority complex.’…the Soviet attitude is one of jealousy as well as emulation and distrust; and the Soviet attitude in Persia has traditionally been on of jealous and suspicious rivalry.” “Power politics are natural and necessary within Russia and in Russia’s relations with the outside world.”

The Soviets conducted monopolistic practices for the fishing industry in the Caspian Sea. “The only important Soviet concession relative to the exploitation of natural resources is the arrangement provided for in the Caspian Sea Fisheries Convention of October 1, 1927…In practice the company has been compelled to sell its products to a monopolistic Soviet distributing company, thus allowing the stronger partner to appropriate the profits itself.”

Trade in the north of the country was strictly controlled, “For all practical purposes the Soviets prevented the Persian government from exercising any control over imports and exports in the North.” The north of Persia is an important part of the country, “…that region comprises the richest provinces of Persia. It includes the second largest city, the most important grain-growing area, most of the forests, all of the domestic tea production, most of the rice, and a large part of the cotton.” “They allowed Persians to travel to and in the North without any special formality; but in the case of persons of other nationalities, the Russian authorities required them to obtain and carry travel permits for each trip.”

Soviets also sought northern oil concessions and their likely goal that was never achieved was to obtain warn water ports in the Persian Gulf. “Russia’s aim has been to obtain outlets through warm water ports.”

Millspaugh elaborates on how Soviet influence was experienced by Persian officials, “Persian officials, whether or not they have been bribed in advance, usually begin negotiations with a conviction that they must surrender in the end. The Russians understand this attitude and maintain an unyielding insistence. If the Persians hold out too long, their ‘northern neighbors’ charge ‘unfriendliness’ or an intent to disturb ‘good relations’ between the two of reprisal and initiate intrigue or bring pressure to get rid of the recalcitrant Persian negotiator and put someone more pliant in his place.” “Whether or not the Russians were bluffing, they succeeded in exposing the weakness of the Persian government and the meekness of the American and British governments.” Unlike the British or Americans, for the Soviets “Chaos serves their purposes better than order.” “The Russians know that in Persia a small organized minority with a definite aim and persistent activity can seize power from a majority that is divided, confused, cowardly, and corruptible.”

American Influence in Persia

Major General Donald H. Conolly in Persia, 1943

In many ways America took over the role of Great Britain in Persia, providing the counter to the influence of Russia to the north. “After Pearl Harbor, an American force, known later as the Persian Gulf Command, under Major General Donald H. Connolly, establish itself in Persia with headquarters at Teheran, and took over from the British the operation of the southern end of the railroad.” In many ways Persians welcomed the presence of Americans as a balancing force that would allow them to maintain independence against Britain and Russia, “Among the Persian people, the better elements of the articulate classes looked to the United States for assistance and protection.”

An American plane mechanic assisted by an Iranian boy working on a light bomber before it is delivered to Russia, 1943

In describing the stance of the United States Millspaugh writes, “The United States stood for equality of economic opportunity and free competitive private enterprise and against totalitarianism, trade barriers, and monopolies.” “The United States wished to promote its trade in this part of the world but frittered away the prestige on which economic as well as political relations largely depend. The United States desired an oil concession; and we would like also airports, contracts for irrigation projects, and possibly an agreement for operating the railway; but the American government permitted the Persians to violate with impunity their contractual obligations to American citizens.”

Although Millspaugh did not have many positive comments for the majority of American diplomats in Tehran, he did praise Louis G. Dreyfous whom served as the 10th U.S. Minister to Persia.

Louis G. Dreyfous

“Mr. Louis G. Dreyfus, who presided over the Legation at the time of my arrival, was generally considered the best as he was the most popular and effective, of the me who had represented the United States in Teheran. The Minister’s wife had captured the hearts of the Persians, not only as a charming hostess, but also as a sympathetic and tireless worker in the slums of Teheran. Daily she took medical care to hundreds of the poor people who live and fester like unclean animals in the caves.”

Mrs. Louis Dreyfus

Millspaugh justifies America’s presence in the country with the following quotes, “Because of our power, our position in the world, and our special relation to Persian, American abstention from interference is a form of interference.” “It is precisely the internal affairs of Persia that must be interfered with if she is to achieve the stability that comes from political freedom and a rising standard of living.”

However, Millspaugh ultimately felt that America failed in its efforts to win over Persia. “In the Persian mind America simply showed weakness…If America is to measure up to its new position in the world, the American people required leadership, informed, unafraid, and unfaltering…Our present organization, dominated by its peculiar state of mind, is perilously obsolete.” “In the strategic area between the Caspian and the Persian Gulf, in the presence of the first massive breach of the Middle East, the United States may already have lost its last opportunity for effective peaceful measures. As total failure approaches, action becomes more difficult and the remaining choices more unpleasant and dangerous.” “…the American Army, if it had been effectively linked into the civilian war and postwar programs, could have been extremely helpful. Unfortunately, the relationship between our diplomatic representation and the Persian Gulf Command contrasted markedly with the essential unity achieved by the British and the Russians.” “Our official attitude in general left Persia left fully exposed to the conditions and influences that had made the country a problem area and an international danger spot.”

Millspaugh felt that ultimately America did not effectively organize its efforts in Persia, a combination of poor leadership and logistical errors essentially allowed the Soviets and a corrupt Persian government to prevent any long-lasting foundation of a democratic and capitalistic society to be laid down. As a result of this Millspaugh predicted that the region would remain one of poor governance and conflict into the future.

A Broken Country

Mrs. Louis Dreyfous meeting the poor living in a slum, 1943

Although there have been positive moments for Persia during the Islamic era, the last time the region was a dominant power in the region was probably during the Sassanid Empire, which ended in the 7th century A.D. How the country and people still exist after a series of massive migrations and invasions over millennia may remain a mystery to some, but the people remain regardless and still hold on to old memories of a strong and powerful culture going back several thousand years. But early to mid 20th century Persia must have been one of the poorest and broken countries on the planet, as Millspaugh describes, “Persia in many respects is where England was in the eleventh or twelfth century, but Persia is spending its political infancy in the presence of twentieth-century civilization and in the midst of a modernity for which she is psychologically and politically unprepared but which she demands and cannot escape. Persia is a child forced prematurely to live the life of an adult…from many points of view Persia is a primitive country and from most points of view retarded.”

“At the beginning of the twentieth century, Persia provided one of the world’s most complete examples of economic retardation and impoverishment, a country in ruins, its resources practically untouched.”

“During the centuries that followed its moment of world supremacy, Persia experienced for longer or shorter periods invasions, civil war, anarchy, famines, epidemics, reigns of terror, and merciless oppression.” Millspaugh was critical of the effects that the Shah’s monarchy had on the population, “It is the so-called modernists, particularly the ex-Shah, who have done greatest violence to the wholesome and functional features of Persian life. Reconstruction must build on the historic foundation. The basic purpose is to release and restore the Persian personality, not to remake it. The idea is not to fit these people into an imported or artificial mould, but to give them freedom and means to live and express themselves.”

“The history of this land conclusively proves the failure of absolute monarchy.”